Another fluid to worry about in a complicated and expensive emission control system.

It’s been said that heavy-duty pickup truck owners who haul and tow frequently have diesel running through their veins. They crave diesel’s high torque at low rpms and extended driving range between fill-ups. Soon, many will have to think about making pitstops for another fluid: urea.

Urea is the same organic compound found in urine, which has forced drivers (at least most drivers) to pause for bio-breaks ever since the car was invented. It turns out that urea, which is being sold under the more marketable name “diesel exhaust fluid,” is also a chemically efficient way to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions produced by diesel engines.

NOx is a major air pollutant that contributes to smog, asthma, and respiratory and heart diseases. It’s a byproduct of diesel’s high combustion temperatures, which results from the high frictional heat levels created by compressing air in the cylinders to the point where it can ignite diesel fuel without using a spark. This is unlike a gas engine, which uses spark ignition to burn petrol.

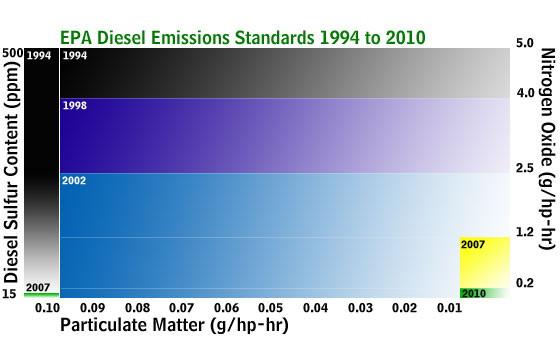

Come 2010, all new diesel-powered pickups will have to meet tougher federal diesel emission standards that will reduce allowable nitrogen oxide levels by 90 percent from today and by 96 percent from 1994.

The third, and newest, approach to Nox reduction is selective catalytic reduction using DEF.

The so-called Tier 2 Bin 5 regulations also mandated the use of diesel particulate filters and ultra-low-sulfur diesel fuel to cut soot emissions by 90 percent in 2007 from 2006 levels. At 15 parts per million, ULSD contains 97 percent less sulfur than the 500 ppm low sulfur diesel it replaced.

There are three ways to lower NOx emissions in diesels: The first is exhaust gas recirculation. EGR recirculates a portion of the engine’s exhaust back into the engine at a lower temperature. The cooled gases have a higher heat capacity and contain less oxygen than air, lowering combustion temperatures and reducing the formation of NOx. EGR is prevalent in today’s clean diesel engines to reduce NOx, but it’s not efficient enough in current form to meet 2010 emissions levels.

Navistar is the only diesel engine manufacturer that says it will use in-cylinder EGR only to reduce NOx next year, but it will be limited to large over-the-road truck applications and not HD pickups and chassis cabs.

The second way is the use of EGR plus a special “adsorber” catalyst material to soak up and break down remaining NOx molecules before they leave the tailpipe. Chrysler is the only heavy-duty pickup manufacturer in the segment to use this approach in its Dodge Ram 2500 and 3500 trucks. The current 2007-09 6.7-liter Cummins six-cylinder diesel powertrain reached 2010 NOx emissions requirements three years early; it will carryover into 2010 and beyond without change in these models while Ford and GM are expected to update their next-generation diesel engines for 2010 using the last technology, below.

The third, and newest, approach is selective catalytic reduction using DEF. The urea-based solution (32.5 percent industrial urea and 67.5 percent deionized water) is held in a separate storage tank and injected as a fine mist into the hot exhaust gases. The heat turns the urea into ammonia that – when combined with a special catalytic converter – breaks down the NOx into harmless nitrogen gas and water vapor.

Like Ford and GM, Chrysler will use diesel exhaust fluid to scrub NOx from the exhaust but only in its new 2010 Dodge Ram 3500, 4500 and 5500 commercial Chassis Cabs.

The Dodge Ram Chassis Cabs use the same Cummins 6.7-liter diesel as the 2500 and 3500 pickups.

You might be wondering why Chrysler is using a NOx adsorber on its HD pickups and urea SCR on its Chassis Cabs. It’s because the NOx adsorber depends on rare earth metals. Until recently, the prices of these metals had been sky high. DEF is much cheaper than rhodium or palladium. The drawback against urea though is it requires periodic maintenance and driver action.

For demonstration purposes, Chrysler had a specially labeled Ram Chassis Cab on the floor at the 2009 Work Truck Show in Chicago to show off its new urea SCR components.

DEF is much cheaper than rhodium or palladium. The drawback is it requires periodic maintenance.

“The 2010 [Ram] Chassis Cabs start with an eight-gallon tank to hold urea,” said Kevin Mets, senior development manager for Dodge trucks. “The eight gallons gives us a good range [approximately 4,000 miles] even though the entire package [DEF plus SCR hardware] weighs about 200 pounds. We don’t rob as much payload capacity as a tank that, say, has a capacity of 16 gallons.”

DEF is expected to cost about $2.75 a gallon when pumped at truck stops and other retailers, according to the North American SCR Stakeholders Group, an ad-hoc industry alliance of truck and engine manufacturers, regulatory agencies and associations, and DEF infrastructure partners and suppliers. It will be packaged in many ways including 2.5 gallon jugs, bulk storage and DEF dispensing units.

Chrysler has located the DEF-fill port on the same side of the truck as the diesel-tank door.

“We put the urea-fill neck on the same side as the fuel neck,” Mets said. “When a guy is at the fuel station, he fills up and can do the urea [simultaneously] so his time into both is the same.”

DEF lines run from the DEF tank to DEF injectors that squirt the urea-water mix into the exhaust stream, behind the diesel particulate trap. There the DEF solution decomposes into ammonia, which mixes with the nitrogen oxide to break down into nitrogen and water. It also cools extremely hot gases exiting the DPF, which acts like a self-cleaning oven during its regeneration process to incinerate trapped soot to begin the soot-trapping cycle again. Coolant lines near the DEF injectors ensure they run at the optimal temperature for the ideal chemical reaction.

DEF starts to freeze around 11 degrees, so heating lines are necessary to keep the fluid warm in very cold weather.

“It kind of goes from a liquid to a slush, like Jell-O, though it would take a long time to freeze an eight-gallon tank,” Mets said.

Heating lines, which use engine coolant, run through the DEF reservoir to warm it up when sensors in the tank determine DEF temperatures are too low.

It may take a long time for the engine to warm up in very cold conditions with sufficient extra-heat capacity to warm the DEF heating lines, especially if the truck is being used over short distances or idling. In that case, combustion temps will also be lower, reducing the amount of NOx created and requiring less or no DEF to clean the exhaust.

DEF fluid may need to be replaced in hot climates where a truck sees little to no use for extended periods. DEF slowly converts to ammonia around 120 degrees, and the process accelerates as temperatures rise.

Of key interest is what happens if the DEF tank runs dry? Chrysler says it will provide plenty of warning to drivers before the truck is prevented from restarting without a urea supply.

“It’s all mileage based,” Mets said. “The [electronic vehicle information center] will show a low-urea/fill-urea warning when there’s a 1,000-mile range left to go. As the driver gets closer [to zero] then the inducement strategy kicks in.”

That inducement strategy includes more frequent use of the low-DEF warning light, chimes that provide auditory warnings and a countdown of how many miles are left until the DEF tank is empty and the truck is immobilized.

“If the countdown goes to zero, then the next stop the driver makes and turns that vehicle off, then goes to restart, he’ll get a ‘vehicle will not restart’ message,” Mets said. “There’s plenty of warning. We’ve got a 52-gallon [diesel fuel tank], which has a range of about 600 miles or less. Eventually he’s got to fill the fuel tank back up, so he has to get off the road and make that stop, and he has to do it at a fueling station that will have a urea system there. It’s all part of the strategy.”

For those thinking of ways to defeat the DEF fluid-level system, don’t. Sensors can determine the composition of the DEF added to the truck, so substitutes like pure water or (ahem) pee can’t be used. The truck will know. It will also detect if you try to mix agricultural-grade urea and demineralized water to brew a homemade batch of DEF.

One concern we had when we saw the demo setup was the placement of the DEF tank below the crew cab, where it rode next to and below the frame rails. Mets said that was the best place to put the DEF reservoir on the truck, so it was out of the way of aftermarket upfitters adding purpose-built job hardware to the trucks. He also said Chrysler engineered the tank to have minimal impact on the truck’s breakover angle for offroad use, and it’s protected off-road by the frame.

Come Jan. 1, 2010, most new diesel pickup truck buyers are going to have to go with the flow when it comes to dealing with urea for clean emissions.

Mike Levine is founder and editor of PickupTrucks.com.