Whether built-in or purchased aftermarket, GPS navigation systems are becoming ubiquitous - but the satellite network that makes them work could soon begin to fail.

“Please, turn left in one-quarter mile.”

By now, almost anyone with an automobile has become familiar with satellite navigation. It’s made it possible for motorists all over the world to find remote and obscure locations – and forget how to get to the nearest 7/11 on their own.

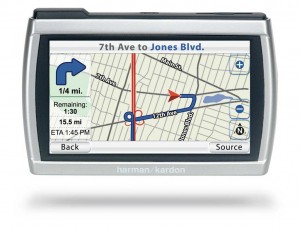

Each year, more and more cars come factory-equipped with “navi” systems, and countless more drivers opt for the windshield-mounted, aftermarket systems that have become some of the most popular gifts at Christmastime, according to retail expects. There are also handheld systems, and even some of the latest smart cellphones, such as Apple’s iPhone, rely on the network of up to 32 mid-orbit satellites that constantly broadcast precise signals that, by comparing several signals simultaneously, can be used to predict location, altitude, time and velocity.

But what happens if the satellites start to fail? That’s a potential problem that could begin to become reality as early as next year, according to a new U.S. government report.

At least 24 of the GPS satellites are needed in orbit to ensure all parts of the planet are covered.

The problem is that the network is simply getting old, but so far, it’s gotten virtually no maintenance by its keepers, the U.S. Air Force.

The first experimental navigation satellites went into orbit back in the 1970s, and the original concept was to provide coded guidance information to the nation’s nuclear bomber fleet. But in 1983, after a Korean Air Lines jetliner strayed over Soviet territory and was shot down by Russian MIGs, then-President Ronald Reagan decided to open the technology up to civilian use. The first automotive application, the Etak Navigator, appeared soon afterwards. By 1994, a full “constellation” of 24 satellites was in office. President Bill Clinton later took steps to improve the accuracy of the signal provided to the public.

While a few satellites have been launched since the beginning of the decade – the most recent in 2008, the Air Force has largely relied on old and increasingly fragile “birds,” according to the report, which was obtained by the British newspaper, The Guardian.

“It is uncertain whether the Air Force will be able to acquire new satellites in time to maintain current GPS service without interruption,” said the report, which was recently delivered to Congress. “If not, some military operations and some civilian users could be adversely affected.”

Prepared by the Government Accounting Office, or GAO, the study cites both mismanagement and a lack of investment, as well as the basic age of satellites that, in some cases, have already been operating well beyond their original design life. It warns that by as early as 2010, some may fail, effectively leaving holes in the radio grid the network uses to surround the globe. Several satellites must be picked up by a GPS receiver simultaneously, their signals compared, through process called trilateration, to calculate location and other information. Too few working satellites and there could be blackouts or, possibly worse, mis-information that could send aircraft and automobiles scurrying in the wrong direction.

The first replacement satellites, originally scheduled to go into orbit in November 2007, have been delayed repeatedly, but the Air Force is aiming for a launch later this year. Whether they’ll get enough of the birds flying in time to keep the Global Positioning Satellite network running smoothly is anything but certain, concludes the GAO report.

Ironically, if the system is left lagging, it could open the door for navi wannabe nations, such as Russia, China and India, which are working to expand competitive satellite guidance networks. The European Union, meanwhile, is preparing its own version of GPS, dubbed Galileo, which could be fully operational shortly.