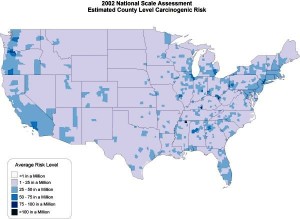

EPA estimates that all 285 million U.S. residents have increased cancer risk at unacceptable levels. Move to North Dakota? Click on map to enlarge.

The wheels of government turn ever so slowly. The Environmental Protection Agency has just released the latest version of what it calls “a state-of-the-science tool” that estimates health risks from breathing air toxics in the United States.

The National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA), based on 2002 air emissions data, helps federal, state, local and tribal governments identify areas and specific pollutants for further evaluation to understand risks they may pose.

The EPA estimates that all 285 million U.S. residents have an increased cancer risk of greater than ten in a million from exposure to air toxics. The average cancer risk, based on 2002 pollution levels, is 36 per million. Levels above a 100-in-a-million risk are “generally unacceptable.” And that includes two million Americans.

This means that, on average, approximately 1 in every 27,000 people would contract cancer as a result of breathing air toxics from outdoor sources, if they were exposed to 2002 emission levels over the course of their lifetime. What has happened since then is not covered in the study.

EPA says that air toxics are of concern because they are known to, or are suspected of, causing cancer and other serious health problems, including birth defects. The report assessed 80 air toxics, plus diesel particulate matter from stationary sources and from mobile sources such as cars, trucks, buses and construction equipment.

The latest study avoids dealing with a critical policy issue regarding diesel engines — whether diesel exhaust particulate matter causes cancer — at the very time car and policy makers are trying to figure out how to decrease CO2 emissions and increase fuel economy.

“In this assessment, the potential risk from diesel exhaust emissions is not addressed in the same fashion that other pollutants are,” EPA frankly admitted. And this TDB report is not meant to be critical of EPA.

The Agency, which has suffered from political interference by the executive and legislative branches since its inception, said “This is because data are not sufficient to develop a quantitative estimate of carcinogenic potency for this pollutant.”

However, EPA concluded that diesel exhaust is among the substances that the national-scale assessment suggests pose the greatest relative risk of causing cancer.

“First, several human epidemiology studies link increased lung cancer associated with diesel exhaust. Furthermore, exposures in several of these epidemiology studies are in the same range as ambient exposures throughout the United States,” EPA said.

In addition to the apparently larger potential for lung cancer risk, there are also “significant potential for non-cancer health effects as well, based on the contribution of diesel particulate matter to ambient levels of fine particles.”

Exposure to fine particles, EPA said, has been linked to significant public health impacts, including respiratory and cardiovascular effects, as well as premature mortality. These effects are not specifically presented in the national-scale assessment analysis, but are considered in setting and implementing EPA’s National Ambient Air Quality Standards for particulate matter.

Translation: Diesel exhaust is problematic and not only increases your risk of cancer and other nasty respiratory diseases, but it can shorten your life.

However, herein is another problem when trying to judge the suitability of diesel use in the U.S., again caused by the age of the data. As newer diesel engines with cleaner exhaust emissions replace existing engines, their health risks should be reassessed.

Maybe they are better. Maybe not.

The 2002 NATA estimates that most people in the United States have an average cancer risk of 36 in 1 million if exposed to 2002 emissions levels over the course of their lifetime. In addition, 2 million people-less than one percent of the total U.S. population-have an increased cancer risk of greater than 100 in 1 million. Benzene was the largest contributor to the increased cancer risks. Benzine is carcinogen released into the air by burning coal and oil. Gasoline refineries, service stations, vehicle exhaust also release benzene.

EPA cautions that NATA provides “broad estimates of risk over geographic areas of the country and not definitive risks to specific individuals. The results are best used to prioritize pollutants and areas for further study, not as the sole basis for regulation or risk reduction activities.”

More information on air toxics: www.epa.gov/oar/toxicair/newtoxics.html