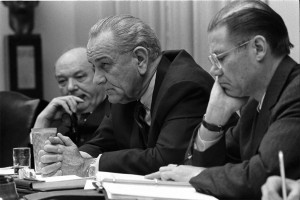

While Robery McNamara, right, with President Lyndon Johnson, was best known for his role in the Vietnam War, he earlier earned a reputation as one of the "Whiz Kids" who saved Ford Motor Company.

Robert S. McNamara died earlier this week at his home in Washington, D.C., at the age of 93. Most of the obituaries ramble on at length about his service of Secretary of Defense during the early years of the Vietnam War — which came to be known, by many, as “McNamara’s War.”

But I want to tell you about his career at Ford Motor Company and argue why I think he could be considered a “car guy” long before his reputation was besmirched by the culture wars growing out of America’s ill-fated adventure in southeast Asia.

McNamara came to Ford in 1946 as one of ten “Whiz Kids” of former Army Air Force statistical analysis and control officers, offered as a package to Henry Ford II who was struggling to rebuild the company after World War II. At the same time, the Deuce was hiring a bunch of dead-ended but highly competent GM executives led by Ernie Breech and engaging in Ford’s first college graduate recruitment program, which yielded Lee Iacocca.

In 1947, McNamara was made a department manager in the Finance Department and two years later advanced to comptroller of Ford Motor Company. Then, on August 1, 1953, just before the introduction of the 1954 models, he was named vice president of Ford and general manager of the Ford Division. He held that position until May 24, 1957, when he became group vice president of the Car and Truck Group, over all Ford’s vehicle divisions-Ford, Mercury, Edsel and Lincoln, the short-lived Continental Division having been folded back into Lincoln by then.

So, as general manager of Ford Division, Bob McNamara presided over:

(1) Introduction of Ford Division’s first modern, overhead-valve V-8 engine in 1954 models;

(2) Introduction of the 1955 model two-place Thunderbird;

(3) Introduction of the 1955 model Fords which analysts of the time believed outsold the ’55 Chevy–although Chevrolet hedged by having its dealers register all their unsold stock just before December 31, 1955, making an end-run around Ford’s true retail sales;

(4) Introduction of the 1956 Ford safety package of standard improved door latches/locks (which Mercedes copied) and concave “deep dish” steering wheel plus optional seat belts and padded dash;

(5) Introduction of the two-sized 1957 Fords that not only beat Chevy fair-and-square in sales but also debuted the Ranchero pickup derived from the two-door station wagon body and the retractable hardtop Skyliner convertible. In those good old days, Ford produced more than 77,000 regular Sunliner convertibles plus another 20,000 Skyliners in the 1957 model year. They’d kill for those numbers today.

Then, as group vice president of the car and truck group, McNamara oversaw both the intro of the Edsel in September 1957 and its dismantling in November 1959 just after intro of the 1960 models. Some undocumented accounts say he opposed the Edsel in its planning stages, but I am skeptical. If he had done so, it would have been because he believed Edsel would steal sales from Ford Division, which was engaged in a sales war with Chevrolet. In the Detroit mentality, winning such wars was overarching.

In any event, as head of the car and truck group, he went on to oversee introduction of Ford’s entry in the heavy truck market in 1958, the segment-pioneering four-place 1958 Thunderbird, the compact 1960-model Ford Falcon in October 1959, the “luxury compact” Mercury Comet in March 1960, the Econoline truck as a 1961 model, the revolutionary (for the time) extended warranties and sharply reduced maintenance schedules of 1961 models, and the downsized and sleek 1961 Lincoln Continentals.

Just after intro of the 1961 models, McNamara was named president of Ford Motor Company on November 9, 1960, only days following John F. Kennedy’s election as president of the United States. McNamara was the first president of Ford from outside the family, but resigned less than two months later to accept Kennedy’s invitation to become Secretary of Defense in his new administration.

Still, his reputation as a “car guy” continued even after he deserted Dearborn for Washington. In the fall of 1961, Ford introduced its “intermediate” Ford Fairlane on a 115.5-inch wheelbase versus the 119-inch wheelbase of the “big” or “standard-sized” Ford Galaxie. As a long-time observer of the auto industry, admittedly somewhat prejudiced from my 25 years with Ford from 1960 to 1985, I believe that Ford’s balkanizing of the auto market in the 1960s, beginning with the intermediates, ultimately led to the downfall of General Motors.

Why? Because ultimately it unraveled Sloan’s “stair-step” marketing concept which had been GM’s money machine for many decades, beginning in 1923. When Ford began offering three sizes of sedans in its showrooms, GM and Chrysler dealers demanded the same. At that point, there was no longer reason for a new car buyer to upgrade from, say, Chevrolet to Pontiac, in order to get more product and prestige.

The word around Ford at the time was that McNamara, believing a niche had been created in the market between the 109.5-inch-wheelbase Falcon and the 119-inch wheelbase Galaxie, conceived the intermediate Fairlane — even to sketching out its key dimensions — while sitting in his Ann Arbor Presbyterian church during services one Sunday morning. I never saw documentation of that, either, but I believe the story. (Remember that the planning had to take place three or four years before introduction.)

It’s rare for top executives to conceive new models. Mostly the ideas start at lower levels and work their way upwards through blessings or denials at various stages and levels of management. Then the division general manager, if he agrees, has to sell the investment to the company’s group VP and he in turn to the CEO and Board of Directors. As group VP, McNamara’s analytical skills certainly would have pointed him to the product hole and his ranking enabled him to direct its filling.

I rest my case. Robert S. McNamara, while he may have been the ultimate in rimless-glasses bean-counters, was also a real car guy. I doubt if even he realized it.

By the way, I urge any readers interested to obtain and study McNamara’s mea culpa about his experiences as Secretary of Defense, In Retrospect. Be sure and get an edition published no earlier than March 1996, which contains third-person rebuttals to some of the self-serving New York Times sniping.

Great history, well told.