On New Year’s Day of 1910, Henry Ford started producing Model T’s at what was then the world’s largest auto factory – the Highland Park Ford Plant. It was an airy complex that would change the world with his new ideas – the moving assembly line, and more than doubling his workers’ pay to the unheard of sum of $5.00 a day.

The assembly line made mass production possible and the unexpected result of boosting his workers’ paychecks meant they could buy his cars and everything else under the sun. Other companies had to compete for the same workers and his employee’s twofold pay increase drove wages up around the country, which stimulated demand.

This true “trickle down” phenomenon gave birth to the modern American Dream of home ownership, plentiful high paying jobs, decent schools and a pathway to citizenship for those willing to do a hard day’s work. There are still lessons to be learned.

“Mass production and the $5.00 day gave the country an enormous boost; it simply made consumers out of almost everyone, in terms of automobiles. The automobile industry was so important to the economy that as it went, the economy seemed to go,” said David Lewis, professor of Business History at the University of Michigan.

The plant that built the cars that put America on wheels, the Ford assembly line, in the Detroit suburb of Highland Park, Michigan.

Today, the fabled factory is hidden behind a strip mall and like parts of the city that surrounds it, it’s a mostly abandoned hulk that occasionally attracts tourists and historians from around the world who come to pay homage to the site that gave birth to modern manufacturing and the rise of the American middle class.

If you didn’t know what you were looking for you’d probably drive by the Model-T Plaza that abuts the crumbling, former administration building with broken windows on Woodward Avenue and not be able to imagine this forlorn site teeming with over 25,000 employees.

People dubbed the factory “The Crystal Palace” because of its vast amount of glass and bright interiors. The factory’s enormous size made people think that Ford had gone mad.

“Frankly, this happened in Henry Ford’s life again and again; he did things that people thought were harebrained, were stupid, were simply flat-out wrong, and most of the time Henry Ford proved to be right. It gave him reason to begin to doubt any of his critics and to believe in his own infallibility,” said Charles Hyde, professor of History at Wayne State University.

To prove his critics wrong, he had to produce and sell an unthinkable number of cars. Within a few years he was turning out so many Model T’s at the Highland Park Plant that it seemed like everyone was driving a Model T.

This was at a time when there was far more competition than there is today. There were over 290 different makes of cars being made in over 145 cities, in 45 states. Michigan had 45 different car companies — 25 in Detroit alone.

But most American and European manufacturers were still targeting the rich. The average price of a car was between $1,500 and $3,000. That would be about $65,000 or $70,000 today. This was beyond the means of ordinary people.

“Henry Ford wanted to build a car that everyone could own. He made a famous statement early on. ‘I will build a car for the great multitude of the finest materials available by the best workmen that can be hired of the simplest design that can be made so that every man with a decent income can take a ride in the countryside and enjoy God’s great pleasures,’ as he put it,” said Lewis.

He redesigned the complete manufacturing process and made it as efficient as possible. No wasted motion. He installed thousands of single purpose machines, many he devised himself, to speed up assembly.

In essence, the factory became one giant machine. The machines and workers were arranged sequentially. The tools and parts were within easy reach. Everything was synchronized. As one part was put on, another was ready. The line kept moving.

It was a relentless pace, but Ford’s costs began to drop substantially. In some cases, the moving assembly line reduced by 80-90% the amount of labor it took to perform a task. Passing those savings on throughout the manufacturing process began to make believers out of Ford’s critics.

“Mass production drove down the cost of producing an automobile dramatically. You can think of all of the developments that have come since — automation, robotics, and what is now called lean production — and none of them had nearly as much influence on cost-cutting,” said Lewis.

As his costs plunged, he lowered his price from $850 to $490 a car. By 1914, he was selling almost 250,000 Model T’s a year.

But his system, reverse engineered from the mechanized cattle disassembly lines that he saw meatpackers use in Chicago, was taking its toll on the employees.

The Highland Park plant had an annual quit rate of over 370 percent. He had to hire 40,000 people a year to be sure he had 10,000 working at all times.

Absenteeism was over 10 percent. More than 1,000 people failed to show up every day, even more on Mondays and Fridays.

This significantly reduced the efficiency of the factory. Once again Ford devised a solution. He created an incentive.

Though the Highland Park plant opened in 1910, it took another three years before Ford introduced the moving assembly line.

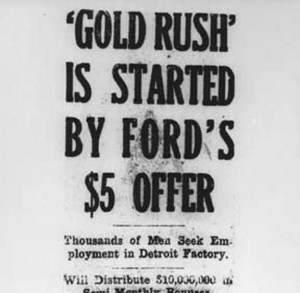

He decided to raise wages to an unprecedented level. In January, 1914, he announced that he was going to pay his workers $5.00 a day. Typical industrial workers were earning about $2.00 a day. This represented an enormous increase.

He also reduced the workday from nine hours to eight hours, allowing employees to earn much more money and work a shorter day.

He imposed some restrictions on his largely immigrant workforce. In order to qualify for the $5.00 a day, the employees had to learn to speak English. He set up schools and made sure they attended. He insisted that they all become citizens and disavow their cultural origins.

At the graduation ceremonies from the Ford English School, there was a gigantic melting pot up on the stage, and the workers who were about to graduate would walk down into this melting pot on a ladder dressed in their native, ethnic costumes — whether it was from Italy or Poland or Greece or wherever — and they would do some kind of quick change and then come out the other end dressed in business suits or plain American dresses, with each worker waving a flag to show their new loyalties.

“Henry Ford was not just building Model T’s; he was also building men, and he was really creating men that were in his own image. In that sense, he really was trying to be a god,” said Hyde.

His god-like industrial wizardry transformed the auto industry and sent ripples through the whole economy.

“How wonderful! A device by which the cost of production could be dramatically reduced, and the customers could get price cuts and the employees could have their wages doubled. We have nothing on the economic scene like that today. Don’t we wish we had,” said Lewis.

Some may decry the unintended consequences of the consumer society but things have changed since Henry Ford’s day. The formula Ford stumbled on had been strengthened through hard fought collective bargaining and, as productivity steadily increased, wages grew. But this grand bargain has been tossed aside. Starting in the 1970s workers’ income started to lose their connection to increases in productivity. Even though productivity has risen dramatically since 1973 wages have been stagnant or falling. At the same time the wealthiest one-tenth of one percent (0.1%) have seen their earnings rise 181%, according to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI). This works out to approximately, $1.7-million a year per person in this bracket. But it’s a paltry pay boost compared to the top one-hundredth of one percent (0.01%) who’ve seen their income rise 497% to $6-million during the same period. These incomes collected by the few have come at the expense of everyone else.

Instead of the American Dream we’ve created a nightmare of stagnant wages, weakened unions, closed factories, jobs shipped overseas, home foreclosures and hateful immigration policies.

“Over the last several years we’ve had an economic policy of making people better consumers instead of helping them earn a better wage,” said Lawrence Mishel, president of EPI. “This fed the credit bubble as it fueled consumption.”

The Economic Policy Institute is spearheading an ongoing program designed to put to rest the notion that Americans are helpless and incapable of doing anything about economic inequality.

“We have to reestablish the connection between wages and productivity growth,” said Mishel. “People get this.”

“There has never been a single reason for Americans to despair of our capacity to improve our condition,” EPI announced when launching its initiative. They’re calling it the “Agenda for Shared Prosperity,” in contrast to the last 30 years of greed.

Anticipating upcoming calls for more tax cuts for corporations and the rich, increased privatization, unfettered pay raises for CEO’s and an industrial policy that puts millions out of work, EPI has assembled a team to make the case that, “the success or failure of the economy is measured not by the value of the stock market or the size of the gross domestic product, but rather by the extent to which the living standards of the vast majority of Americans are rising.”

As we celebrate the centennial of the factory that created the American Dream, it’s time to dedicate ourselves to renewing this dream. They said Henry Ford was crazy to believe in the impossible. He proved his critics wrong and I believe we can do what some consider impossible today. Let’s get busy. Happy New Year.

Michael Rose is a documentary filmmaker based in Los Angeles. You can find more about his work, and learn about the world’s great cars, at www.greatcarstv.com. Follow Michael Rose on Twitter: www.twitter.com/MichaellRose

This piece first appeared in The Huffington Post.