Volvo’s plan to offer a plug in hybrid vehicle (PHEV) on one of its larger car lines by 2012 is just the beginning of an ambitious program to spread the technology to its entire lineup by the end of the decade – if not sooner – according to insiders working on future products at the Swedish company.

The Volvo plan arises from CO2 emissions reductions dictated by stringent European Union regulations. These are twice as tough as the controversial CO2 reductions that are now being implemented in the U.S., which call for a 35.5 mpg fleet average in 2016.

At the lighter end of the line, starting with the C30 BEV, a pure battery electric vehicle, will also be offered in Europe at the same time.

Plans for exports of PHEVs and BEVs are still flexible, executives say, and are dependent on the price of fuel, as well as government taxation and subsidy policies governing the marketing of electric cars.

The vast engineering development, manufacturing and sales programs required for electrification are being undertaken against the background of a depressed, profitless global industry, where loss-making Volvo Car is being sold by its parent, Ford Motor Company, to the Chinese maker Geely.

Successful and, more importantly, profitable implementation of electrification now appears key to the survival of all auto companies given the current regulatory environment, which shows no signs of decreasing demands for more fuel efficient and therefore less CO2 belching vehicles. The fact is companies and customers no longer will control their own fates as things are now shaping up. Regulation will dictate a large part, if not all of the market, and survival of companies will depend on how they can comply with an unprecedented amount of government direction.

Smaller companies such as Volvo face a larger challenge in surviving, arguably, if nimbleness as well as possible exemptions and/or company friendly regulation are not ultimately more decisive factors.

Viewed one way, the Volvo commitment to hybrids is a stunning reversal of the traditional disdain that European makers expressed about this Japanese developed technology. All European, and for that matter U.S., automakers are well behind current developments in the ongoing hybridization of the auto industry, which has been underway for more than a decade now.

Toyota is now producing its third generation of Prius (albeit with a nickel metal hydride battery) and has numerous other hybrid models on sale, while Honda is on its second generation Insight. Both of those companies are far along with the development of the next step, plug-in hybrids and lithium battery hybrids. Toyota is clearly leading all makers in spreading hybrid technology almost universally across its Toyota, Lexus and Scion lineups.

Viewed in a broader perspective, the emerging Volvo electrification plan, which will require expensive changes in the crash structure of its automobiles renowned for their safety, is just the latest indicator on how the regulation is dictating the cars that people will be able to buy in the future.

It’s also a sign of the collapse of auto companies’ political clout to protect themselves and (perhaps) markets since regulation is backed by consumer sentiment (or vice versa) and is forcing companies to abandon, or at least heavily modify, traditional engineering and marketing strengths at great expense.

At stake for car companies is the satisfaction or worse, the dissatisfaction of future buyers, if a brand strays too far from its previous known essence and the implied promises carried over into newer products.

Nonetheless, the European Union is moving ahead — over automakers’ protests — with CO2 standards for passenger cars that dictate a reduction in average CO2 emissions from new cars to 120 g/km. (Proposed U.S. standards are roughly twice as high.) Fewer than 9% of the cars sold in the EU in 2006 met this level of emissions, the latest data available t me.

The costs of complying with a CO2 standard of 120 g/km through vehicle technology are estimated at about €3,600 ($5,108) on an average per car, according to makers.

Naturally, there are complicated credits and exemptions or special treatment for cars bought by the wealthy in play – not only in Europe but also in the U.S., as the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Transportation work out how proposed rules will actually be enforced.

While there’s a phase-in for the EU standards, it appears extremely ambitious – 65% of new cars will comply with requirements in 2012 when the first plug-in hybrid Volvos appear; 75% in 2013; 80% in 2014 and 100% in 2015.

Since CO2 emissions are directly proportional to the amount of any carbon-based fuel that is burned, CO2 limits are in essence fuel economy requirements for almost all vehicles. Here, it is difficult to make clear comparisons since Europe calculates fuel economy on a liter of fuel consumed per 100 kilometers driven, different units and the opposite approach of our miles per gallon method.

However using rough conversions, the 2015 EU standard is more than 45+ mpg on a fleet average, with a proposed EU 95 g/km standard for 2020 the U.S. equivalent of , oh, 65 mpg.

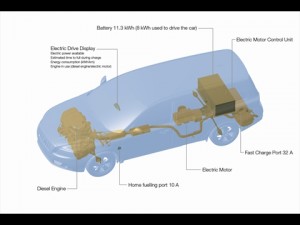

The Volvo plug in hybrid that will appear in 2012 in a V70 will be rated at 1.9 liters of fuel consumption per 100 km, and emit less than 50 g of CO2. With a 50 km range on electric power alone, the large car could be rated at 100 mpg. And, depending on the jurisdiction, the fuel economy credit against the required average could be more than that. Hence, the sudden rush at all automakers to electrification.

Actual consumer demand for such a vehicle is unknown and subject to intense debate. Every study that I am aware of shows that consumer expectations are wildly discordant with the performance and the price of upcoming electric vehicles. So just how much EVs can contribute to CO2 reduction remains dependent on how many are actually are put in use.

Moreover, car companies are facing huge incremental costs for vehicles that will not provide consumers with any tangible benefits compared to existing ones – and indeed will cost more and possibly have less range. Makers are hoping that massive taxpayer subsidies will ease the transition. Environmentalists and other pressure groups also are pushing for subsidies.

Ken,

Of course there will be teething pains as we electrify powertrains.. but I believe your assertion that PEVs will be “vehicles that will not provide consumers with any tangible benefits compared to existing ones” is fundamentally incorrect. The operating costs will be less given electricity is most often far less expensive than gasoline and electric powertrains have the potential to be more reliable and durable. In a future article, can you explain further your thoughts and data sources that led you to make this assertion so it can be explored further? Thanks!

Dave: Will do, or at least try (we have already explored aspects of this in many of our previous postings.

In my view operating costs are only part of total life costs which are dependent on initial costs plus ongoing costs compared to other powertrains and vehicles. Here the payback can be very long – years beyond the average new car lease — before break-even is reached even at fuel prices much higher than $2.50/gallon. (If payback is ever reached.)

No argument from me on electric motors, or at least industrial ones now in use, compared to internal combustion engines they do last a long, long time with little maintenance. And regeneration will greatly extend brake life, although the calibration and consumer acceptance are controversial — see our NHTSA / Prius stories.

The life and cost of the power electronics and battery packs, or even a single lithium ion cell used in these batteries are another matter though.

Yes, this needs much more discussion, and I will try to provide it.