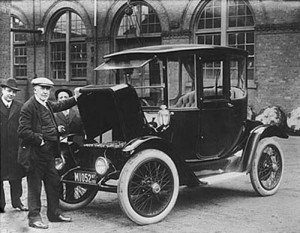

Thomas Edison looks over a battery-powered Ford, favored by some early motorists, including Henry Ford's wife Clara.

Everything old is new again, goes the old refrain, and nowhere is that more true than in the auto industry. Though they may seem high-tech, primitive navigation systems first appeared in the earliest days of the 20th Century, and fuel-saving CVT transmissions date back even further.

Then there’s the electric vehicle, which has suddenly became the hot topic on this year’s auto show circuit. But if you’d been around for the first big U.S. car show, a century ago in New York, you’d have discovered there were as many battery-powered vehicles as those running on gasoline. Even Henry Ford got into the act, producing an electric flivver for his wife Clara, and asking old buddy Thomas Edison to try to come up with a longer-range battery.

“They’ve been around really for the past century or so, but they really haven’t had mass-market appeal,” suggested the industry pioneer’s great-grandson, and now Ford Motor Co. executive chairman, Bill Ford Jr.

Will they now? That’s the big question that the Ford heir raised at the close of this year’s annual conference of automotive executives and engineers, the SAE World Congress.

The modern electric vehicle, using the latest in lithium-ion technology, “appears (to be) the biggest came-changer” in the industry, said Ford, during an SAE speech.

He noted that the maker is lining up five vehicles that can run, at least for moderate distances, on battery power alone – a figure that doesn’t include conventional gas-electric models, like the Ford Fusion Hybrid.

Motorists might like the near silence of battery vehicles, like the Nissan Leaf, but that could pose a safety threat to pedestrians.

The first on tap will be a lithium-powered version of the Ford Transit Connect, followed by a battery Focus. A series of plug-in hybrids will follow. They’re designed to run on battery power during commutes and around-town runs, but a back-up gasoline engine can kick in for longer drives, once the batteries are drained.

Of course, Ford isn’t alone. General Motors will take a plunge into electrification, later this year, when it launches the much-anticipated Chevrolet Volt. And earlier this week, senior Volt project leaders acknowledged they are looking at other vehicles that would use what they’ve dubbed their Voltec battery car platform.

(Click Here for that story.)

Nissan, meanwhile, will begin producing a pure battery-electric vehicle, or BEV, the Leaf, later this year. And even Mercedes-Benz is getting charged up about electric power, with battery versions of a variety projects starting to fill its line-up, all the way up to a lithium-powered version of its $300,000 SLS AMG supercar.

But while battery technology may be seen as a real breakthrough for the environment, there are those who warn the technology does have a downside. The good news is that battery power is quiet.

The bad news is that battery power is quiet, so much so it “could potentially put pedestrians at risk,” warned another SAE speaker, NHTSA Director David Strickland, “especially blind pedestrians.”

While BEVs are still a rarity on the road, there’s enough data from 12 states on car-pedestrian crashes involving hybrid-electrics, like the Fusion Hybrid and Toyota Prius, to show they “do have a significantly higher incident rate,” said Strickland, when operating in electric mode.

Pedestrian crashes are already a significant factor, accounting for as much as 10% of annual vehicle fatalities in the United States. How to reduce that problem is already something that automotive engineers are addressing.

Volvo’s newly-updated 2011 S60 will introduce Pedestrian Detection with Full Auto Brake. The system uses a complex set of algorithms to not only identify pedestrians but determine if they might walk into the vehicle’s path. If need be, the onboard computer will jam the brakes, quickly bringing the S60 to a complete stop.

But such costly technology isn’t likely to show up on every battery car, at least not in the near-term. NHTSA, Strickland said, is studying other solutions, including ways in which makers might be able to warn pedestrians, and one possibility is to mandate a minimum “base level of sounds at low speeds” that would clearly signal a car is coming.