Talk to me. The next big safety breakthrough could come from having vehicles talk to each other - a concept called IntelliDrive.

It seems like such a simple concept: get cars to talk to one another and they should be able to not just save fuel, but also save lives. Yet as a group of sometimes disagreeable panelists proved at an industry confab, this week, simply getting people to talk about how to interconnect tomorrows cars is a difficult challenge.

Then again, designing the technology could be the easy part.

Most experts actually seem to agree that technology allowing cars to communicate with each other — and the infrastructure – could make our highways safer and more efficient. But they disagree about who should have access to vehicles’ computer systems – and at what level. Right now, automakers rigidly control access to the automotive operating system in a way that even Apple Computer might find constricting.

Frank Weith, technology strategy manager in the Electronics Research Lab at Volkswagen of America, said the automakers are reluctant to give access to the vehicle’s systems. But what became increasingly clear during a session at this year’s Management Briefing Seminars, in Traverse City, Michigan, is that they may need to.

“The firewalls have to shift,” said John Waraniak, vice president of advanced vehicle technology strategy for the Specialty Equipment Market Association. “Open frameworks are the way forward.”

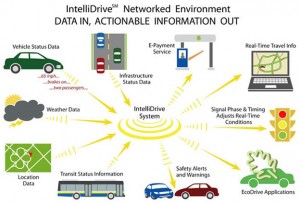

Connected vehicles represent a huge range of technologies where vehicles will interact with each other as well as infrastructure, such as stoplights and systems that monitor traffic flow, to improve safety, reduce emissions and even allow municipalities to operate more efficiently.

A connected vehicle would be safer because it would know when another vehicle is running a red light, for example. It would be more efficient because it could communicate with traffic lights, allowing it to shut off its engine until the light changes. They could help cities and counties more effectively apply road salt by determining where vehicles are slipping, rather than just indiscriminately blasting the area with salt.

Robert Bertini, deputy administrator for the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Research and Innovative Technology Administration, said much of the technology exists to make connected vehicles a reality now. The key will be taking the creativity of the developers of smartphone apps and applying it to connected vehicles.

In the U.S., the collaborative connected vehicle movement is called IntelliDrive. He said that by 2013, the USDOT must decide about requiring Dedicated Short Range Communications (DSRC) receivers in vehicles or possibly develop another communications system.

Bertini said there are many questions to answer about IntelliDrive including privacy concerns, the ability to opt out, how it will be governed and funding.

While those issues are debated, testing of smart vehicle connections is under way. For example, Kirk Steudle, director of the Michigan Department of Transportation, said new traffic lights that are part of the current Telegraph Road reconstruction project in the Detroit suburbs will be equipped with DSRC communication devices.

“This will be the first place anywhere with traffic lights set up, giving you that information,” Steudle said.

Count Kieran O’Sullivan, executive vice president for infotainment for Continental, among those who want to see more of the technology installed faster.

“Now is the time to start implementing, not just having field tests,” O’Sullivan said.

The University of Michigan, Michigan State University and Michigan Technological University have been awarded a total of $12.2 million in research grants to help develop the system.

While the technology to make connected vehicles certainly exists, experts say it won’t be easy to pull together.

“I haven’t seen an area that is more challenged,” said James Vondale, director of the Automotive Safety Office at Ford.

One of those challenges is getting American car buyers to pay more for safety systems. Typically, Americans have only shown an interest in paying for more in-vehicle entertainment.

“Making safety affordable is a key element,” Vondale said.

The experts are also concerned about standardizing the warnings drivers might see from these systems. For example, one system could warn a driver about a vehicle running a red light by flashing a red light on the instrument panel, another one could have a constant yellow icon and still another could use a system that vibrates the seat.

James Sayer, associate research scientist for the U-M Transportation Institute said the fledgling industry needs to adopt standard practices, nomenclature and communication standards.

“Standardization is going to become critically important,” Sayer said.