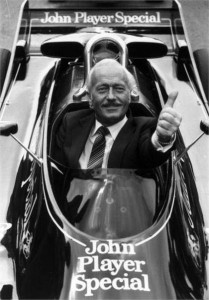

"To add speed, add lightness," said legendary car driver and designer Colin Chapman, founder of Lotus.

The late Colin Chapman, the revered race car and sports car designer, is often credited with the quote “To add speed, add lightness.” If he were alive today, he’d likely put more emphasis on that maxim than ever as a central tenet in the push for better fuel efficiency.

Chapman, founder of Lotus Cars, was known for his clever techniques to reduce weight in both his race cars and road cars. His belief was that a light car could beat more powerful ones because its chassis would handle better. And he was right. Lotus won seven Formula One Constructor titles under Chapman.

Today’s automakers face a far different challenge than Chapman. Instead of speed, auto companies are working furiously to increase fuel economy, but most of the work is focused on more efficient powertrains, not reducing weight.

Jay Baron is amongst those who think they’re making a mistake. Baron, president and CEO of the Center for Automotive Research, an industry think tank, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, said reducing weight might be even more important than increasing powertrain efficiency because no one knows what powertrain technology will win out, but lighter vehicles will help with efficiency no matter what is powering the car.

A primary way to save weight is using lighter materials. Baron said there are essentially five materials in play here:

• mild steel, which is the predominate material in most cars, costing about 30 to 50 cents per pound.

• high-strength steel, which is about double the cost of mild steel but can be made thinner to provide the same strength.

• aluminum, which costs about $1.50 per pound, but is significantly lighter than steel. Besides the cost disadvantage, it’s more difficult to form and weld.

• plastics, while the prices vary wildly based on material and purpose, plastic is far more expensive than other materials and takes longer to mold.

• magnesium is another material finding its way into vehicles, but it is even more expensive than aluminum.

The biggest problem, Baron said, has been the inability of material suppliers to work together on parts that use more than one type of material. Many automotive parts, such as steel-reinforced rubber, use more than one type of material.

Baron said he has tried to work with the leaders of the trade associations representing those material makers.

He said that vehicle engineers have told him they don’t care what type of material they get to do the job; they just want to build a car that meets the performance characteristics specified by the automaker that can be sold at a cost that buyers will pay.

Baron said that many suppliers of the raw materials are doing great work independent of each, but they could do more together.

“My criticism of the industry is those material sectors don’t work together,” Baron said.

For example, steel producers are reluctant to work with the suppliers of other materials because steel is the primary material for a car and suppliers don’t want to lose that business, he said.

Baron said he is working to bring members of the trade associations for the different materials together, telling them that he can get them in to see the engineers if they agree to work together. Baron said that because he is not tied to any of the material makers, he can offer an unbiased approach.

The European automakers, particularly Audi and BMW, are far ahead of makers from Japan and the U.S. on creating lightweight vehicles. He said European drivers demand better performance, sharper driving dynamics and have the added issue of expensive fuel.

“The European market is more motivated for a lighter vehicle,” Baron said.

Absent from Baron’s list of the most important lightweight materials is carbon fiber. Baron said that a current price of about $10 per pound, it’s too expensive for most cars. He added that carbon fiber would be attractive to automakers if the price dropped to $5 per pound.

Carbon fiber is expensive, so it might be perfect for a manufacturer such as Lamborghini, which announced last month that it had opened a carbon fiber development center staffed by 30 people. The Italian supercar manufacturer already uses carbon fiber for some components of its Gallardo and Murciélago supercars. Lamborghini is owned by Volkswagen, so some of the technology could trickle down to VW’s mainstream brands.

Another technique to reduce weight is optimizing the vehicle for a single type of engine instead of the typical of four- and six-cylinder options available in most mid-size sedans. John Krafcik, president and CEO of Hyundai Motor America, said the company’s designers saved 40-50 pounds by eliminating the V-6 option in the mid-size Sonata because the engine bay only has to be designed around a smaller four-cylinder engine. Only 10% of buyers were expected to opt for the V-6.

But reducing heft goes beyond lightweight materials and optimizing the structure for a single engine type. Clever packaging can also have a positive effect on weight.

For example, the BMW M3 Coupe weighs in at 3,600 pounds, compared to a Cadillac CTS-V Coupe, which weighs 4,260 pounds. Part of that advantage is due to the smaller, less powerful engine in the M3, as well as the lightweight materials BMW uses.

But it’s also worth looking at the overall size of the vehicles. The M3 is almost 7 inches shorter in length, 3 inches narrower and half an inch shorter in height, but still has interior and trunk volume that are on par with the Cadillac or better.

Baron also pointed to a study by Lotus Engineering where the company redesigned the Toyota Venza crossover for a 38 percent weight reduction with just 3 percent more costs. A major benefit is a projected 23 percent improvement in fuel economy. Lotus did the study on computers, not on a real model, so it’s difficult to say if this car could pass U.S. crash standards or hold up to the abuse all vehicles must sustain. But still, the numbers are compelling.

Baron said that reducing weight usually costs $2 for every pound that is eliminated. But the benefit is 7 percent better fuel economy if weight is reduced by 10 percent.

Alan McCoy, a spokesman for Ohio-based AK Steel, said steel is likely to continue as the material of choice because of its low cost. The high cost of materials other than steel might be better suited for high-end vehicles in the near-term, he said.

“It’s hard to see the minivan skinned in carbon fiber anytime soon,” McCoy said.

Still, McCoy said the steel industry is open to partnering with manufacturers of other materials.

“When it makes sense, I think that’s an idea,” he said.

Vehicle lightweighting techniques are beginning to show up. One example is the Ford MKT’s liftgate, which is made of aluminum and magnesium. Ford said that lightweighting will be a major part of its efforts to improve fuel efficiency, accounting for as much as 50 percent of the automakers fuel mileage gains.

To reach that goal, Ford and other automakers will have to find ways to use lightweight materials, but also package their cars in clever ways to maximize space.