There was a time when an automaker like Buick would have to build scores of sheet metal prototypes for no other reason than to run them into a wall – or, more precisely, a barrier used for running safety tests.

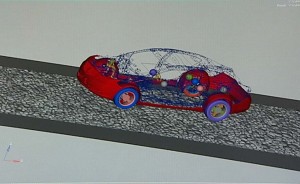

These days, however, manufacturers have transferred most of their initial safety testing to digital simulators that are so accurate only a few of these hand-built prototypes, which often cost several $100 thousand each, are needed – and then only to prove to cautious government regulators the data are accurate.

So, if you can build a car that’s safer while rolling down the road, what about building a virtual road that will help make the car not just safer but quieter, more comfortable and more fun to drive?

That’s what Buick claims to have done with a new digital system that can simulate much of what normally requires months of driving at a test track. Want to see what happens when that new model hits some Belgian blocks? How about a patch of Michigan potholes? Just tap the keyboard and sit back as the simulation begins.

“Just like a photo scanner, we can scan the surface of a road to create a three-dimensional digital representation,” explains Mine Tasci, a Turkish native, who has worked with a team to come up with an innovative system using lasers and cameras to create a 3D model of all sorts of road surfaces.

A trip to the General Motors Proving Grounds, in Milford, Michigan will reveal that the maker has long tried to simulate what motorists might face on a daily basis, from some of the potholed stretches that give Michigan a bad name to the nearly impassible road leading up to the Cerro del Cubilete shrine, in Mexico.

Even the best cars will squeak and rattle there, says Tasci, “Customers who drive on that road complain about steering rack noise. That’s why we wanted to recreate this road so that we can test and ensure that our vehicles are up to the challenge of driving on roads like this one.”

GM isn’t the only maker trying to simulate real world road conditions. Many makers are using cameras and onboard sensors to create virtual roads. At Ford, for example, the data is then programmed into a computer that controls a “shaker.” At its essence, the device has four posts, one for each wheel on which a vehicle prototype sits. The electromagnetically-operated system then jounces the vehicle as if it were riding down a particular stretch of roadway, even though it never leaves the lab.

One of the advantages of going completely digital is that engineers can simulate a vehicle’s performance long before the first prototype is ever built. By the time the rubber meets the actual road significant development work has already gone into the project and – Buick hopes – resolved issues that might not show up for months in real world testing.