Few have left such a legacy on the car world as David E. Davis. The knee-jerk response is to dub him the “dean of automotive journalism.” But knowing David for the entirety of my career I would assume that should this copy have fallen into his hands he’d have quickly struck that out as clichéd.

There will be plenty of words spoken about David E. Davis in the coming days. One cannot ignore the passing of a legend who had so much influence on the automotive world in his 80 years, right up to his death over the weekend.

Yes, he has often been called the “dean,” and by no less than Time magazine. Elsewhere, it has been said, David “entirely and single-handedly defined…automotive journalism in the post-Vietnam war era.”

Davis himself suggested that his skill was “his ability to marry southern story-telling to big-city presentation.” Journalists are, by definition, story tellers. But few could so effectively captivate and hold the attention of an audience, even those who cared little to naught about automobiles. Perhaps the closest I can think of with such a skill is Garrison Keillor, the host of NPR’s Prairie Home Companion.

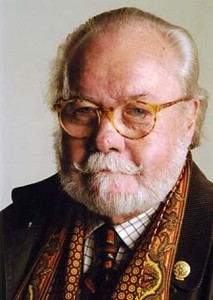

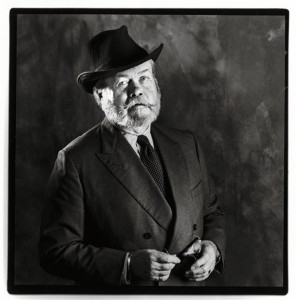

With the white beard – and girth — that sometimes rivaled St. Nick, eyes that alternately twinkled and pierced, and the trademark waxed moustache that added a touch of a smile even to the most cutting remark, Davis was one of those who seldom was lost in the crowd.

I last saw him less than a month ago, at the black tie gala at the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance. David had lost a significant amount of weight as the result of the preliminary treatment he was receiving for bladder cancer. (He would ultimately succumb to complications following surgery for the disease.) He was a bit more mellow and reflective, but if he feared the possible dangers he kept it hidden, matter-of-factly discussing the doctor’s prognosis as if it were another road test. Only David could make the risks seem almost humorous.

But that was his way with words. Some writers are succinct, some effusive. Others have a consistently memorable way of turning a phrase. In his own remembrance on Autoblog, Chris Paukert notes that David was likely to ask, “Is your life a rich tapestry?” rather than offering the simple and meaningless, “How are you?” Paukert was one of the lucky ones to have begun his career under Davis and, in the process, learn that writing about cars could be an art, as well as a trade. (Click Here for Paukert’s tribute.)

Davis taught that to readers, as well, through a number of media outlets he managed and occasionally created over the years. Those included all the major “buff books,” as auto insiders like to call Car and Driver, Road & Track, Motor Trend and Automobile, the latter the magazine he founded two decades ago, against seemingly all odds.

David E., as most called him, might have retired on the hefty paycheck he eventually received from Rupert Murdoch when he sold Automobile, but he had far too much to say and offer, and a curiosity that kept him going right through his final days.

And where others from the golden era of automobile journalism fled in horror or fought vainly the ongoing emergence of digital media, David E. Davis embraced and explored, helping get Winding Road up-and-running. Most recently, though, he had returned to Car and Driver as a columnist.

While David will be most well remembered as a journalist, he was a man of many hats and helmets. He spent much of his early career, in fact, in automotive advertising. For Campbell-Ewald, Chevrolet’s long-time agency, he could claim credit for helping craft the long-running tagline, “Baseball, hot dogs, apple pie and Chevrolet.”

“Sophisticated” and “worldly” are likely two words that will also show up in the inevitable tributes and obituaries of David E. Davis. Yet he began life like so many other migrants to the once-great Motor City. He was born on November 7, 1930 in a home in Burnside, Kentucky that didn’t even have running water – his family moving north in search of the opportunities offered in Detroit during the days when it was the “arsenal of democracy.”

In his early years, Davis took plenty of career detours, selling mens clothing, among other things, and only signing his first column for Car and Driver at the age of 32. “By that time, I had worked in four automobile factories, sold cars in three imported-car dealerships and one Packard showroom,” he recalled when he wrote his return column for C/D in May 2009. He forgot to mention that, in his early years, his real passion was motor sports. And he was good, too. But in a race when he was 25, David E.’s car flipped over, dragging him face first down the tarmac and leaving him horribly disfigured.

Years later, he would recall, “I suddenly understood with great clarity that nothing in life — except death itself — was ever going to kill me. No meeting could ever go that badly. No client would ever be that angry. No business error would ever bring me as close to the brink as I had already been.”

David knew well the odds as he battled serious cancer for the second time, but perhaps knowing the extra days he had been given he went on with his life and work, as always, with a flair and a flourish that few could come close to matching.