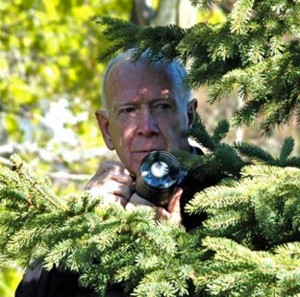

His name is Dunne. James Dunne. And if Ian Fleming had written about the world of automotive espionage, this is the man who might have served as his role model. But where some spies sleuth for competing car companies, this septuagenarian Grosse Pointer serves a more noble purpose. Or so he’d prefer to think. The fact is, you’ve probably seen some of his work over the years in the pages of monthly magazines, in countless newspapers around the world, or on various internet sites, including TheDetroitBureau.com. Jim Dunne is the undisputed king of automotive spy photographers.

Dunne insists he’s retired – though the spy shot of the 2013 Nissan Altima he provided us with yesterday suggests otherwise. (Click Here for that story.) It’s a way of life and not something someone easily walks away from…especially if they still keep a camera close at hand.

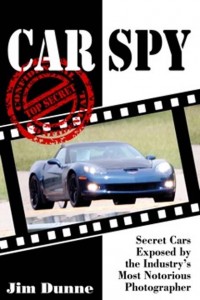

As accomplished a story-teller as he is with the camera, Dunne is finally revealing some of the secrets of his successful career, captured in his new book, “Car Spy,” which you can find via Amazon.com. (Here’s the link to buy a copy.) We’ve done a little spying of our own, however, and nabbed one of the more interesting chapters, the story of Dunne’s incursion into the top secret GM Design Dome. Here’s the excerpt:

The theme of this story is “quid pro quo.” I thought it could easily lead to disaster, but the Pontiac buck-room incursion ended up, in the retelling, being one of my favorite adventures.

Back in the late 1960s, I had figured out a scheme for getting into Pontiac engineering’s inner sanctum, the place where they put together, by hand, their future models. My ultimate goal on this trip was to get inside the so-called buck room. That’s where future cars were displayed in parts—bucks—some with complete front clips including grilles and headlights, some with fully outfitted cabins to examine measurements such as seating clearances. Other assemblies checked steering-wheel and instrument-panel clearances for correct sight lines and ease of operation. No complete car was seen here, just the sections that needed real-life verification of fits, finishes, comfort, roominess, and general convenience.

I knew from an earlier unauthorized visit to the Pontiac engineering building that the buck room had three complete front clips, which include bumper, grille, hood, fenders, and headlights. I knew there were fully finished bucks of the upcoming 1970s Grand Prix, Bonneville, and Firebird. Never mind the complete car; if I could get those front clips on film, I’d make a good profit.

The plan was to walk past the receptionist while carrying a clipboard under my arm and a collection of pens in the pocket protector of my short-sleeved white shirt—typical engineer’s getup in those days. A narrow dark necktie completed the disguise. In my pocket was a camera.

Above all, I didn’t want to be discovered. It could mean a trespassing charge or, worse for me, loss of employment and a black mark on my résumé. These things are important. Timing was important, too. I figured noontime was my best bet, since employees would be going back and forth for lunch, and working spaces would usually be left unguarded.

Once inside and past the receptionist, I’d go down the back stairs to the basement. I had been there before; I knew the way. The problem would be if I were recognized [IS1] deep inside the building. That was troubling. I would lie awake nights worrying about the consequences. After all, I had a wife and seven youngsters to feed.

Pontiac’s buck room was a large engineering bay in the basement, a high-ceilinged room with the floor space of a basketball court. It was accessed through a common-size steel door that was left unlocked during working hours.

The first part of my plan worked perfectly. I assumed my best too-busy-to-be-questioned attitude, got past the receptionist and down the stairs to the bay, pushed open the door, and checked out the collection of bucks in various stages of assembly. I saw no employees, and I entered. The sight that greeted me was startling, a true mother lode of Pontiac’s plans for the coming years. As I expected, there were big Bonnevilles, the completely changed Firebird, Trans Am, Tempest, Lemans, and some revised Grand Prix, all scheduled for introduction some two or three years hence.

One of Dunne's biggest scores was capturing this Chevrolet Corvette -- landing him a number of cover stories around the world.

I used my Minox camera to good advantage, snapped each front-clip buck in turn, with one eye out for the entrance door to open.

My mission was accomplished in a couple of minutes, and I was just about to leave when I noticed a movement in the back seat of one of the bucks, one near the back wall. A head popped up and looked straight at me. I knew I was busted. The head belonged to a minor Pontiac PR executive who recognized me.

I palmed the Minox, hoping that it hadn’t been spotted, and turned to get out the door and out of the building. I wasn’t going to stop, no matter who tried to grab me.

Car spies have become a reality for the automakers -- who now go to great lengths to disguise their future products while still testing them out in the open.

But then another head popped up from the rear seat of the buck, this time a female-type head. She was one of the secretaries who worked in the Pontiac offices. She saw me, I looked at her, I looked at the PR man, he looked at me, he looked at the secretary.

Many decisions were made, and an agreement was silently reached among the three of us in a couple of milliseconds. There was no need to make up a story or even answer an embarrassing question, let alone think up a lie.

I confidently turned and strode to the door. I made my way up the stairs, walked out to the parking lot, and drove off the Pontiac property. The Minox shots were instant hits on the spy-photo market. To this day, I haven’t revealed the names of the rear-seat buck testers, nor have they ratted on me. That’s quid pro quo.

About the same time I was shooting the Buck Room, Pontiac was developing the sensational Grand Prix model. The GP was a hurry up project at Pontiac. When one of the GP designers came up with the idea of stretching the front end of the Tempest, squaring off the body lines, and creating a special two-door model, John Z. DeLorean, Pontiac’s chief, was impressed. “Get this ready for the directors’ meeting on Monday,” John Z. ordered. Starting that Friday and working through the weekend, DeLorean’s people had a wet-paint model of the car ready for showing. The directors were impressed, John Z.’s instincts were vindicated, and the car came to be a huge success for Pontiac. But not for my purposes. That hurry up weekend left no hands idle in the Buck Room. So even if I was aware of the Grand Prix project, I couldn’t get inside to snap some pics of Pontiac’s soon-to-be strong selling line.