A new study suggests the federal government’s decision to increase the amount of ethanol in gasoline could have “adverse results,” which several industry trade groups say translates into the likelihood it could wreck some engines.

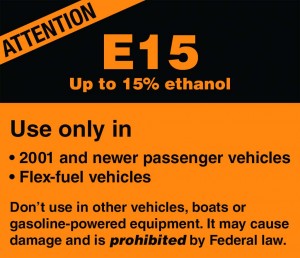

Federal regulators last year upped the percentage of ethanol it wants used in gas from 10% to 15% — what’s known in the trade as E15. While many of today’s vehicles can handle that and even go up to an 85% blend of the alcohol-based additive many trade groups, as well as classic car owners, howled in protest, warning that the increase might cause damage to older vehicles.

They also cautioned that other gas-powered machines, such as marine engines, lawn mowers, generators and chainsaws could be damaged.

A new study by the Coordinating Research Council, or CRC – a trade group supported by eight major global automakers – warns that the critics are right. While the make-up of the CRC might lead some to question its motives, and thus its findings, the study was actually conducted by FEV, a company that has long served as a consultant to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The study suggests that using 15% alcohol at the pump can result in a wide range of engine problems, including valve damage, loss of compression, diminished performance and lower fuel economy.

Noting that older vehicles and most powered equipment were not designed to tolerate a higher level of ethanol, Mitch Bainwol, the president and CEO of Auto Alliance, warned that “many vehicles on the road today are at risk of harm from E15. The unknowns concern us greatly, since only a fraction of vehicles have been tested to determine their tolerance to E15.”

The findings are being disputed by Growth Energy, another trade group representing ethanol producers, which derided the findings of the new report as “inaccurate.” It pointed to studies conducted by the EPA itself that failed to show harm – as well as to the use of E15 by NASCAR, racing teams experiencing “the benefits of increased performance and horsepower.”

Growth Energy is, however, at the heart of the ongoing flap, having petitioned the EPA in 2009 to allow the increase in the use of ethanol. That fit a mandate from Congress, which had set significantly higher targets for the use of the alcohol fuel – much of it currently derived from corn and other food stocks. The goal is 36 billion gallons by 2022, but as of 2010 actual use had only risen to 11 billion.

The EPA initially took a Solomon-like stand, in October of that year approving the use of E15 for cars produced after 2007. But after running its own studies the agency rolled that back to cover vehicles from 2001 and beyond.

Proponents claim ethanol will help the nation sharply reduce its dependence on foreign oil. Skeptics contend that alcohol-based fuels actually reduce a vehicle’s mileage. And they contend that the push for ethanol has more to do with the demands of farm state lobbyists than any real environmental or geo-political issues.

The CRC says it took eight pairs of engines spanning the 2001 to 2009 timeframe and ran them through identical 500-hour durability tests intended to replicate what those engines would experience after 100,000 miles of use. It noted that of those run on E15, two had measurable mechanical damage with another showing a sharp spike in emissions.

A statement by two Washington, D.C.-based automotive trade groups, the Auto Alliance and Global Automakers, warned that such damage could cost from $2,000 to $4,000 to repair and asked the EPA to back down on the new E15 mandate.