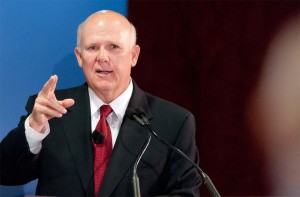

General Motors Chairman and CEO Dan Akerson recently let his guard down for a brief moment, hinting GM made a mistake by not selling off its Opel brand back in 2009, shortly after the U.S. giant emerged from bankruptcy.

Apparently, a growing list of analysts and other observers would agree, warning that the U.S. maker simply won’t be able to stop the hemorrhaging of the German-based Opel which is now heading for a 13th year of red ink.

“One of the worst things in the auto industry is owning a cash-burning, resource-consuming business,” warns Adam Jonas, lead auto analyst for Morgan Stanley, who has now downgraded GM shares to “overweight,” largely due to the continuing problems the maker has in Europe. “We believe the time has come for GM to find a new home for Opel.”

Following its emergence from Chapter 11 in July 2009, GM negotiated a deal with a Russo-Canadian consortium led by mega-supplier Magna International in which the U.S. maker would have relinquished majority control of Opel. The deal was pushed by former CEO Fritz Henderson and was reportedly one of the factors in his ouster. Akerson, then a GM board member, was strongly in favor of keeping the European maker, contending it could be fixed.

But a planned turnaround failed to materialize last year, resulting in the ouster of GM’s Europe’s senior management team. Their replacements less than a year before Stephen Girsky, himself a former Wall Street analyst and now GM Vice Chairman, was assigned to work out a new revival plan. Like Akerson, Girsky was in favor of keeping Opel.

In an interview in May, Akerson declared the European situation “a 4-alarm fire” before briefly suggesting he may have made a mistake in 2009. But he quickly stressed that he wasn’t someone interested in hindsight but, rather, only had time “for looking at what’s ahead of me.”

What’s ahead may not be much better. Details of Girsky’s turnaround plan have emerged — but it appears that, due to a variety of factors, necessary steps such as plant closings and job cuts would need be phased in over several years, arguably not soon enough for most observers.

In the meantime, Opel had a $617 million deficit for the first six months of 2012 and a report by London-based Barclays projected another $900 million in red ink for the second half of what is certain to be Opel’s 13th consecutive year of losing money.

That’s despite some preliminary steps to ease the financial strain. The powerful German union IG Metall recently agreed to 20 short workdays, a rarity in that country, something that could save Opel about $50 million.

But the maker is still going to be burdened by tremendous excess capacity and won’t be permitted to close one of its German plants until mid-decade.

Of course, Opel isn’t alone. The European auto industry, as a whole, is in dire shape. GM’s French ally, PSA Peugeot Citroen, is reportedly seeking a government bailout. Peugeot’s own problems have limited the potential payoff of a deal it negotiated with GM earlier this year.

The problem is that “nobody wants to be first” to take the “necessary steps,” said Fiat/Chrysler CEO Sergio Marchionne, in an interview last month. The first critical move would be sharp capacity cuts by most makers operating in Europe, he indicated.

Three years ago, when GM appeared ready to dump Opel, Marchionne indicated an interest in acquiring the money-losing subsidiary. Asked whether he’d still consider a bid, the executive responded, “There was a window of opportunity for Opel and it opened and it closed.”

With the original Magna deal no longer viable, it is unclear who, if anyone, might now step in – especially without a commitment to permit major changes from IG Metall.

As a result, Morgan Stanley’s auto analysts acknowledged, “We believe GM must bear the cash burn and management distraction for a while longer.”

But the new report stressed that the financial losses, as well as the management distraction, caused by Opel could be the most serious risk GM will face following its bankruptcy.