“Hydrogen is the clean, efficient power for the future,” goes the old joke among engineers, “and it always will be.” Like the sign that offers “free beer…tomorrow,” it’s a cynical sign that while hydrogen power could ultimately be one of the cleanest possible sources of energy, it never seems to quite reach the mass production stage.

Yet, there are small but telling signs that this may soon change. A growing number of automakers are planning to launch limited production of vehicles using hydrogen fuel cell technology. General Motors, meanwhile, has moved its hydrogen research center in an upstate New York outpost to one of its main Detroit engineering campuses.

And Dept. of Energy Secretary Steven Chu has signaled a growing interest in hydrogen after earlier dismissing the technology and shifting more than $100 million in federal research money from fuel cells to batteries.

Hydrogen seemed all the rage within the auto industry at the dawn of the new Millennium. And a cursory understanding explained why: the lightweight gas is the most abundant element in the universe and, when used in a fuel cell system, produces electricity and water vapor rather than the harmful emissions found in the exhaust of an internal combustion engine.

The energy produced by a fuel cell stack, meanwhile, could be used to run the same sort of motor drive system found in today’s electric vehicles. But, since a tank of hydrogen could readily be refilled in a matter of minutes – rather than the hours it takes to charge up an electric vehicle – proponents often referred to the fuel cell as a “refillable battery.”

Sounds good on paper, anyway, but “you need four significant technological breakthroughs,” Sec. Chu said after joining the DoE in 2009. “If you need four miracles, that’s unlikely. Saints only need three miracles.”

The primary problems are that:

- While hydrogen is abundant, it is always found in a chemical form, such as the hydrocarbons that make up gasoline, requiring lots of energy to free up the gas;

- Distributing hydrogen is technically complex and there’s no mass infrastructure in place to rival today’s gasoline station network;

- Storing hydrogen onboard a vehicle is costly and difficult; and

- Fuel cells remain expensive and difficult to mass produce.

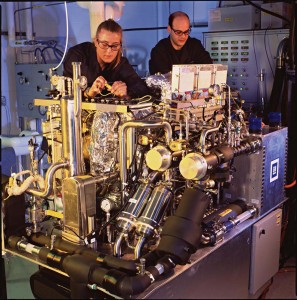

Despite such challenges, proponents insist steps are being taken to come up with all four “miracles.” GM researchers, for example, believe they can remove most of the rare metals, such as platinum, needed to make a fuel cell stack work efficiently, bringing the price of the raw materials down in line with that of the catalytic convertor found in all modern gasoline-powered automobiles.

Nissan – perhaps the most active proponent of battery cars – signaled its reviving interest in hydrogen power during the recent Paris Motor Show where it unveiled the TeRRA, a hydrogen-powered SUV concept.

Senior executive Andy Palmer, who oversees Nissan’s electrification program, noted that fuel costs have fallen by roughly 80% and suggested the Japanese maker would be ready to put a vehicle like TeRRA into production “whenever hydrogen becomes widely available for consumers.”

Honda was the first automaker to market fuel cell vehicles to consumers. But the FCX was offered for lease only in a select portion of Southern California close to the handful of hydrogen fueling stations now open to the public. The maker’s CEO Takanobu Ito recently revealed plans to launch a second-generation fuel-cell car in 2015 that will be offered in both Europe and the U.S.

Toyota Vice Chairman Takeshi Uchiyamada confirms the Japanese giant will have its own fuel cell sedan on the market by 2015. The maker sees the technology as a way to sidestep the limited range and long charging times associated with battery cars.

Though he remains skeptical, Hyundai Motor America CEO John Krafcik confirmed his company will also produce a hydrogen car starting in 2015. Details have yet to be released, however.

Mercedes-Benz is in the midst of a small California-based fleet test of its F-Cell hydrogen vehicle. German makers have been particularly supportive of the technology, in part, because of the financial backing of their government. Berlin recently approved a multi-billion Euro program that would set up a network of hydrogen filling and battery charging centers across that country.

Detroit makers were early proponents of hydrogen power and GM once promised to have its first fuel cell vehicle in production by this year. All three have backed down – in part because of the cash crunch of the recent recession but also because of shifting interest that had favored battery technology. But with electric vehicles gaining little traction in the market – and the White House reviving its own emphasis on hydrogen power, that could be changing.

GM will be moving its fuel cell research center from the small NY state community of Honeoye to its main powertrain research campus in Pontiac, Michigan. This could signal a belief that hydrogen power has a real opportunity to become viable for production – and that Washington could be shifting focus.

(Click Herefor more on the GM fuel cell center’s move.)

Slate magazine reports that, “John Hofmeister, the former president of Shell USA and the incoming chairman of the Energy Department’s technical advisory committee on fuel cell vehicles, said (DoE Sec.) Chu made supportive remarks about the potential for hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles while speaking at a recent, closed event.”

It remains to be seen how much backing Washington will actually give the technology – something not likely to be clarified until after the November presidential election.