To many of those in the Motor City, even a century after it was founded, the nation’s second’s largest automaker is still known as “Ford’s,” a reference to the family that founded it and to the men who have run it.

Indeed, Ford Motor Co. still has a family member at its helm, William Clay Ford Jr., the great-grandson of founder Henry Ford. But day-to-day operations are in the hands of an outsider, Alan Mulally, who has proved himself one of the most capable senior managers in the company’s history. And for that, both Mulally and shareholders might want to offer a little thanks to 93-year-old Philip Caldwell, who died this week nearly 28 years after retiring from Ford Motor Co. as its very first chairman and chief executive not to carry the Ford family genes.

“Philip Caldwell had a remarkable impact at Ford Motor Company over a span of more than 30 years,” said Bill Ford, Executive Chairman, Ford Motor Company. “Serving as CEO and later as Chairman of the Board of Directors, he helped guide the company through a difficult turnaround in the 1980s and drove the introductions of ground-breaking products around the globe. His dedication and relentless passion for quality always will be hallmarks of his legacy at Ford. Our thoughts and prayers go out to his family.”

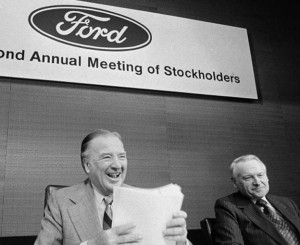

Caldwell became Ford president in 1978 and the chairman and CEO in 1980 following the sudden retirement of Henry Ford II, the grandson and namesake of company founder Henry Ford — but only after the equally unexpected ouster of Lee Iacocca, long the heir-apparent.

Caldwell was a sharp contrast to the flamboyant the man known to many as “the Deuce.” The Massachusetts-born Ford lifer was best known for his down-to-earth management style and for his financial acumen rather than bring the classic Detroit “car guy.”

It was a methodical, sometimes almost plodding approach honed perhaps when, as a Navy lieutenant in World War II, Caldwell was in charge of moving ordinance to follow the troops as they moved from one island to another across the Pacific.

Not everyone appreciated that approach. Critics called Caldwell and his ilk “bean counters” and fretted that their focus on finances rather than the product the company sold would never allow it to overtake competitors like General Motors or, at the time, fast-rising Japanese competitors like Toyota.

But to others, Caldwell brought a level of much-needed discipline in the wake of the Deuce’s often capricious management style, something that became increasingly anachronistic as Ford faced a new world order centered around globalization and vicious competition from the imports.

But in hindsight, Caldwell proved to have enough of a sense of what the company needed to bring onboard the folks who could design the right products. Under his watch, first as head of the then-new Ford truck operations, the maker took control of the pickup segment with the F-Series – a full-size line that has been the nation’s best-selling vehicle for decade. But equally important, as chairman and CEO, he oversaw the development of the Ford Taurus.

The original midsize sedan was a breakout product, introducing a wide range of features not seen before, whether in domestic or foreign sedans. Its distinctive, aerodynamic design – chided by some as “jellybean styling” – transformed the industry, influencing automotive shapes for decades to come. And it became the last American model to lead the sales charts in the critical midsize sedan segment.

At the official media preview of the Taurus, a lavish and well-attended event on the MGM studio lot in Los Angeles, Caldwell was to give the keynote address. Known for his rigid mannerisms, which meant little deviation from well-scripted presentations, a senior public relations handler convinced the white-haired executive to “toss away” his notes and speak off the cuff.

As he began his speech, Caldwell did precisely that, throwing his text over his head, only to realize he didn’t know what to say next. His few brief, impromptu comments were, the PR counselor later laughed, perhaps the shortest and best speech Caldwell ever gave.

But Caldwell had the last laugh because the Taurus — known by some as the “you-bet-the-company” car — became a smash success that saved Ford at a time of deep financial trouble.

And behind the scenes, Caldwell could go with the proverbial flow and knew how to respond like a street fighter to the often highly-charged, political atmosphere in Ford’s executive suites. In fact, his biggest success might have been his ability to remain in the good graces of the Ford family, climbing to the top after the Deuce famously fired Lee Iacocca in 1978 with the explanation, “I just don’t like you.”

Following his retirement after 32 years with Ford, Caldwell remained active, primarily in the financial world. He was a Senior Managing Director at Lehman Brothers from 1985 to 1998. And he served on numerous corporate boards, including Chase Manhattan Bank, Digital Equipment Corp, Macy’s, and The Kellogg Company, as well as on many non-profit, business, and governmental advisory boards.

Caldwell succumbed to a stroke at his home in New Canaan, Connecticut, where he moved after leaving Ford nearly three decades ago.

RIP.

As far as the Taurus…another strange name for a car, it was more like a Camary in that it offended a lot with it’s weird styling but it was priced right and thus appealed to the mass market who care more about price than looks.