Henry Ford first tied cars together by rope, yanking them along the line, but within a year was running an assembly line much like those we see today.

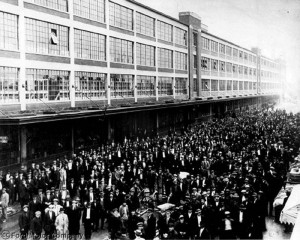

It’s little more than a crumbling ruin now, a decrepit collection of brick buildings in one of the poorest neighborhoods in Motown, but the old Highland Park Assembly Plant was once the site of an industrial revolution, one rivaling the invention of the steam engine in terms of its impact not only on Detroit or the U.S. but, indeed, the entire world.

Historians have long argued about exactly what date that revolution actually occurred, but next Monday is the day that Ford Motor Co. plans to mark the occasion that founder Henry Ford’s first moving assembly plant began rolling.

“The assembly line made almost everything we have today possible,” says Matt Anderson, curator of the automotive collection at the independent Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. While it might have first been used to mass produce Ford’s Model T, today, he adds, “It affects a lot more than just the automobile.”

The invention of the assembly line helped put America on wheels - and create the middle class market that supported Ford's factories.

The Model T actually went into production in 1909, well before the Highland Park plant opened, Henry Ford’s goal to provide an affordable car for the masses, and at an initial $820, the so-called Tin Lizzy was a lot closer than most of the other handmade vehicles of the day.

“But the real issue was how to make the Model T in the volume, and at the price people could afford,” says John Fleming, the executive vice president of manufacturing and labor relations for Ford Motor Co.

(Crowdsourcing campaign aims to save historic Ford Model T plant. Click Herefor more.)

Even moving into the newer and much larger Highland Park plant didn’t allow Ford to keep up with demand. He needed a process that worked more efficiently than having teams to workers each build one Model T at a time. He found the answer in the slaughterhouses of Chicago and Cincinnati, explains museum curator Anderson.

They were known as “dis-assembly lines,” he recalls, beef carcasses hanging from conveyor belts with each worker along the way assigned to slice off a specific cut of meat. When Ford managers discovered the process, they turned it around. Starting as little more than a basic frame, the Model T was pulled along by a moving conveyor belt. Specific parts were delivered to each station were workers would assemble a single piece of the vehicle, over and over again.

The reason for the debate over the actual starting date is largely the question of when the massive plant was completely transformed to handle the new process. Ford initially experimented by pulling partially assembled vehicles along by rope, then added an endless chain. It was early 1914 before the plant was completely converted, says Dr. Jim Womack, co-author of the seminal book, “The Machine that Changed the World,” and head of Boston’s Lean Enterprise Institute.

Whatever day one chooses to mark for the Centennial, in the early days, working the assembly line was a grindingly repetitive and physically challenging process and the turnover in the plant was constant. But the process allowed Ford to go from building dozens, then 100s of Model Ts each week to rolling out one a minute or more. His company was able to slash the price of the “flivver” to as little as $260 by 1923, even as he encouraged workers to stay on the job with the then-revolutionary offer of $5 a day in wages.

Millions of Americans were soon able to buy their own horseless carriages and tens, then 100s of thousands found work either on the assembly lines popping up all over the country or the parts plants supplying them. It was a major factor in the creation of both a consumer society and of the middle class able to afford the goods those factories produced. And other industries quickly adopted the Ford moving assembly line process, but here and abroad.

(Happy Birthday, Dear Henry. Ford’s founder would be turning 150. Click Here for a look back at the automotive pioneer.)

There have been attempts to find alternatives, particularly approaches that aren’t so numbingly repetitive for workers. A number of Swedish firms, including carmaker Volvo, and even General Motors in the U.S., tried a concept known as cell manufacturing where small teams do a variety of tasks, rather than handle single parts. The approach has had, at best, limited success, and most manufacturers have returned to the moving assembly line.

“I think Henry Ford would probably think the modern assembly plant isn’t very different from what he developed at Highland Park,” contends Womack.

That said, there have been plenty of changes made. Today, robots routinely work alongside humans, particularly in the gritty body shops where heavy steel pieces are welded together into bodies and frames. And gone are the days when someone with lots of muscle but only the most rudimentary education can land a job on the line. Factories that once might have employed 5,000 now can get by, in many cases, with 1,500 or fewer pairs of hands, and workers’ brains are tapped to ensure quality and productivity are at peak.

The question is what the assembly line will look like in 25 years, never mind another 100. Ford Vice President Fleming believes there will still be a role for humans, contending there’s only so much more automation possible. “In my opinion,” he contends, “We’ve got the right balance.”

That said, Paul Mascarenas, Ford’s chief technical officer and vice president, notes there are plenty of new “Technologies such as 3D printing, robotics and virtual manufacturing (which) may live in research but have real-world applications for tomorrow and beyond.

Indeed, low-cost 3D printers already allow consumers to produce a variety of complex objects that, in the past would have only come off an assembly line.

(One of the plants that anchored the “Arsenal of Democracy” could soon fall to the wrecking ball. Click Here for more.)

Prof. Womack, meanwhile, says there’s always room for new techniques that can increase efficiency and quality. In recent years, for example, suppliers have begun delivering parts to the line sometimes minutes before they are needed – and often in precisely the sequence workers will assemble them.

That reflects one subtle change over the past century. Henry Ford, famous for offering customers the choice of “any color, as long as it’s black,” knew that simplicity was key to factory efficiency. But today’s automotive plants often produce not just a variety of colors but numerous different models of varying sizes reflecting the consumer’s demand for increased variety.

“The scale of operations” may shift to accommodate the market, says Womack, with smaller plants based closer to consumer. Plants producing 250,000, even 500,000 vehicles annually? “I don’t see that 50 years from now,” he predicts.

As for the old Highland Park Assembly Plant? It might actually be around, at least what’s left of it. A regional development group recently staged a successful grassroots fundraiser to purchase key buildings, and new grant money is in the works that could eventually turn the factory into a museum celebrating the day the world was changed – and the machine that changed it.

Portions of this story first appeared on NBCNews.com.