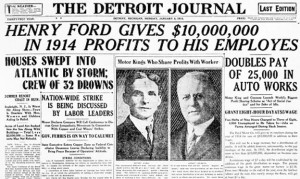

Looking back in history there are plenty of events that helped shape our collective modern life, such as the inventions of the light bulb and telephone. But perhaps no single moment was more pivotal than a day exactly 100 year ago when Henry Ford announced he would double the pay for 25,000 of his employees.

Not only did Ford boost wages to $5 a day but he cut the time his employees spent toiling on the grueling assembly line from nine to eight hours.

He was hailed by workers – and inundated by 10,000 job applicants who raced to his Model T plant in the Detroit suburb of Highland Park. The industrialist also was derided by many of his manufacturing colleagues, some declaring him a socialist, others warning that the added costs could bankrupt the Ford Motor Co.

Over 10,000 applicants gathered outside the Ford plant in Highland Park after the wage hike was announced.

Clearly, that didn’t happen and, if anything, it helped lower Ford’s costs by reducing the chaos on the assembly line where workers frequently had lasted little longer than it took them to be trained for the job.

Equally important, Ford’s $5 wages – about $117 a day today, or nearly $30,000 a year – helped kick-start the American middle class, creating a ready market for the cars those workers were building, especially when other major manufacturers were forced to follow suit.

The Ford Motor Co. was already more than a decade old when Henry Ford made his bold move. But what really permitted him to boost pay was another major development that occurred just three months earlier.

Priced at barely $800, the Model T – the Tin Lizzy to fans – was an overnight sensation, but Ford struggled to meet booming demand even after moving into the sprawling, multi-story Highland Park plant. It quickly became apparent that building cars the old fashioned way, workers assembling each vehicle by hand at fixed stations, wasn’t going to work.

So, in October 1913, Ford connected a line of Model T sedans by rope and dragged them through the plant, stopping long enough at each new work station for each employee to perform a series of tasks, over and over. It was the birth of the moving assembly line. And, by the following winter it was clear the process worked well enough to dramatically boost the plant’s capacity – and the amount of work each employee could generate, justifying the January 5th pay hike.

(Click Here to learn more about the centennial of the moving assembly line.)

“Up to that bold moment in January, no business had ever nodded to the importance of the labor in such a dramatic and costly way. The $5 Day marked, if any one date could, the end of the Gilded Age,” ,” historian Douglas Brinkley noted in his book “Wheels for the World.”

It also transformed Henry Ford himself from just another industrialist into one of the most well-known and influential men in America, a role he embraced as he became increasingly outspoken about topics ranging from home life to the need for the nation to stay out of the first World War – Ford initially mounting an ill-fated peace mission but later lending his factories to support the war effort once America was drawn into the battle.

(Group launches effort to save Ford’s old Highland Park plant. Click Here for more.)

While not all of his employees qualified for the $5 wage, all received major increases and the payoff was obviously almost immediately. Previously, the Model T plant saw as much as 10% of its workforce quit – daily. That quickly dropped to just 1%. By 1915, even though production was rising sharply, Ford needed to hire just 2,000 replacement workers. In 1913, the year the moving assembly line was switched on, the factory had needed 53,000.

No wonder, Ford himself referred to the pay hike as, “the greatest cost-cutting move I ever made.”

Meanwhile, even as competitors raced to copy Ford’s new manufacturing system, the automaker was finally beginning to meet up with demand, boosting production to an unprecedented one vehicle per minute. For the next decade, the Ford Motor Co. would be the world’s largest automotive manufacturer, a position it lost only because of the Ford patriarch’s stubborn refusal to replace the Model T when new competitors – notably General Motors – came along with newer models offered in more colors and with more features.

And while Ford had once been a hero to his workers he would eventually be villainized for the harsh conditions along the line. The automaker aggressively resisted union organizing efforts, giving in only after media coverage of the violent Battle of the Overpass, when goons beat up labor activists outside one of the Ford plants in May 1937.

(Several other early manufacturing relics could get a new lease on life. Click Here for more.)

Over the decades, wages at Ford and its Detroit rivals would rise rapidly – until the U.S. economy began to falter in 2007. That saw the United Auto Workers Union agree to trim total labor costs at Ford from around $70 an hour to just over $50. And many newly hired workers now fall into a lower, or second-tier pay structure worth little more than half that amount. That means they’re earning less today, adjusted for inflation, than Ford workers were given after the pay hike of January 1914.