By the end of next year, at least three automakers, Honda, Hyundai and Toyota, will be offering U.S. motorists new fuel-cell vehicles running on hydrogen rather than gasoline. They bill the technology as an environmental breakthrough, the first step towards what some are calling a “Hydrogen Society.”

But while hydrogen may be the fuel of the future, fuel cells have a surprisingly long past. The technology got its first serious use during the Apollo moon mission, and actually dates back to the mid-19th Century. Indeed, many of the technologies now showing up on today’s most advanced vehicles actually have a long history dating back decades and, in some instances, centuries.

The idea for the automobile itself can be traced back at least to the days of the Roman Empire when a self-propelled carriage — powered by tightly wound human hair, much like a rubber band – was driven into the Coliseum to entertain 3rd Century Emperor Commodius.

It’s not unusual for scientists and engineers to come up with great ideas that show tremendous promise but just can’t be put to practical use. That’s been the challenge that automotive manufacturers have faced since the days before Henry Ford finally figured out how to make a workable moving assembly line.

(Local Motors aims to revolutionize the auto industry by 3D printing its new ReLoad car. Click Here for the story.)

Many of the features just working their way into the automobile are benefitting from the development of new materials, but the real breakthrough is the microprocessor that seems to make almost everything work a little more efficiently.

Take the big V8 in the Chevrolet Corvette. It can yield as much as 31 miles per gallon on the highway, the sort of numbers not long ago associated with economy cars, not high-powered sports cars. One of the tricks is a system called Displacement-on-Demand. When the ‘Vette is cruising along, half of its cylinders can shut down, reducing fuel consumption.

GM first introduced the concept three decades ago as the V8-6-4 on several Cadillac models. The engine was supposed to switch between eight-, six and four-cylinder modes, but without today’s electronic controls it was so rough and unreliable most owners had the system disabled.

(Despite slumping sales, Nissan CEO Carlos Ghosn confident EVs will go mainstream. Click Here to learn why.)

The new Mercedes-Maybach S600 features a technology called Magic Body Control. It uses a camera system mounted on the windshield, behind the rearview mirror, to scan the road ahead. It automatically adjusts the big luxury sedan’s shock absorbers, among other things, to soften out the bump of a pothole.

Carl Benz invented the modern car but in 1770, Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot demonstrated a working steam carriage he called the fardier a vapeur.

Nissan tried to offer a similar concept in 1988 on its Maxima sedan using sonar sensors mounted under the car, but the technology simply wasn’t yet ready for prime time.

A number of new vehicles, such as the redesigned-for-2015 Honda Fit, use Continuously Variable Transmissions. Instead of the normal fixed, or step, gears you find in automatics and manual gearboxes, a CVT uses a tightly-stretched belt to link two, cone-shaped shafts, one connected to the engine, another to the driven wheels. By adjusting the position of the belt and shafts, you can run the engine at or near its optimum speed, depending on whether you’re looking for performance, fuel economy, or the best blend of both.

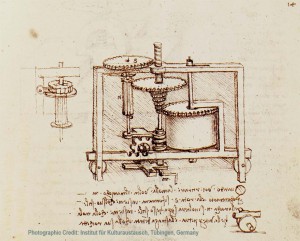

Drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, in 1490, show the concept of a CVT. Milton Reeves put the idea to practical use for saw mills in 1879. And by 1900 several attempts were made to use it in a car – about the time Charles H. Duell, then director of the U.S. Patent Office, declared “Everything that can be invented has been invented.”

Maybe he was right. Millions of cars are now sold each year with onboard navigation systems, while countless more motorists use aftermarket “navi” devices. The first satellite-based system, the Etak Navigator, was introduced in 1984 by Nolan Bushnell – better known as the man behind the Atari videogame system.

The primitive Iter Avto navigation system used scrolling paper rolls mechanically linked to a car's wheels.

But a primitive navigation system appeared about eight decades earlier. It used a speedometer-like cable to track how far a vehicle had driven and to turn a player piano-style roll. Instead of striking notes, however, the system would turn a toy car mounted in a box on top of the dashboard signaling when to turn. The system was highly inaccurate and could only be used on a handful of pre-selected roads.

With the fuel cell, Welsh physicist and attorney William Gove is generally given credit for inventing the first fuel cell stack, which combines hydrogen and oxygen to create electric current. The first significant application was to provide power for those manned Apollo capsules. Automakers have been tinkering with the technology ever since and some believe hydrogen cars will replace batteries and gasoline alike as tomorrow’s clean alternative.

(Are automatics, DCTS and CVTs set to replace the manual transmission? Click Here to find out.)

As for the car itself, the Romans apparently never could come up with a way to make that hair-powered concept practical. American inventor Oliver Evans got a little bit further with his crude steam-powered dredge, Orukter Amphibolous, set to work in Philadelphia’s busy harbor in 1805. He even charged curious onlookers a quarter to see it work. But it wasn’t until the German Carl Benz came along in 1885 that the first practical car rolled down the road.

Ever since, inventors and engineers have been struggling to add new technologies to make driving safer, faster, more fuel-efficient, comfortable and fun.

(This story first appeared on NBCNews.com.)