When the lithium-ion battery in a car like the Nissan Leaf or Tesla Model S runs down you have to find a charger to plug into, a process that can take 10 hours or more. But a new Israeli start-up hopes to market an entirely new type of battery that you’d “charge up” or, more accurately, refill at a conventional service station.

And while the “Alunergy” battery would create no CO2 or other harmful emissions, it does produce a high-demand chemical byproduct that can be ready resold – meaning users could wind up actually getting paid back for using it, according to the inventor who hopes to commercialize the concept in the next couple years.

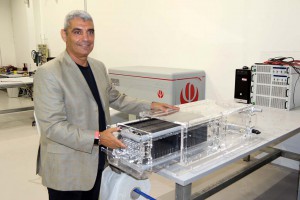

“We want you to feel smart by seeing how much money you’ve saved,” said Aviv Tzidon, the CEO of Phinergy, which is based in a suburb of sprawling Tel Aviv.

(EV industry expected to hit nearly $60 billion by 2021. For more, Click Here.)

The basic concept being developed by Phinergy isn’t entirely new, but life-long entrepreneur Tzidon believes it has finally come up with a way to commercialize a lithium-ion alternative known as the aluminum-air battery.

The concept operates quite differently from a familiar, rechargeable battery. In fact, it can’t be recharged in the conventional way.

The Alunergy battery starts out with small sheets of pure aluminum that are bathed in an alkaline electrolyte and water. The process is extremely energy dense – it produces a high level of power for a given mass. In theory, a kilogram, or 2.2 pounds of the lightweight metal can generate 8.1 kilowatt-hours of electricity. In practice, it produces about half as much – which is still significantly more power than a lithium-ion battery, Tzidon explains, or, for that matter, from burning coal.

In the process, the aluminum sheets are steadily converted into a compound called aluminum hydroxide, That material has numerous uses, such as in water purification, as well as for fireproofing plastics and building materials.

The battery Phinergy is developing would allow a motorist to drive as much as 1,500 miles or so before the aluminum would need to be a replaced. To do so, explains Tzidon, could be done in a minute or so, by swapping out the plastic pack that contains the metal. For the typical American driver clocking 12,000 miles a year, that would mean a swap-out about eight times a year.

The motorist would also have to replace or, more accurately, exchange, the electrolyte, typically every 450 to 400 miles. That would be about once a week or two, Tzidon added, suggesting that, “We are imitating the experience of gasoline.”

(Click Here to see how another Israeli battery company hopes to solve one of the biggest gripes about EVs.)

The solution isn’t used up, like a conventional fossil fuel, but once it is full of that aluminum hydroxide it would be swapped for a fresh solution stored in a tank, much like gasoline. The old electrolyte would then be put through a machine developed by aluminum giant Alcoa that separates out the contaminant.

The alkaline mixture could then be reused. The aluminum hydroxide, meanwhile, would be resold and, according to Phinergy’s business plan, the money it makes for that high-demand chemical would be shared with both the service station and the motorist.

“We’re looking at a new era of energy,” with a very different business model, Tzidon said during a tour of Phinergy’s labs.

Each fill-up would cost more than charging a lithium-ion battery. But the Alunergy pack, Tzidon forecasts, would itself cost about half as much, even with the cost of lithium technology plunging. So, in the end, a vehicle would be cheaper to buy and, when all is worked out, the aluminum battery would be significantly less expensive on a per-mile basis. He estimated the technology could be cost-competitive even with gasoline if oil were again to fall below $30 a barrel.

The concept relies on a number of key assumptions. For one thing, Phinergy envisions producing the aluminum it needs in places like Iceland or Northern Ontario where abundant renewable energy sources are available. Iceland already has become a major source of the metal because of its access to cheap geothermal power.

Phinergy claims to be working with a number of potential partners, including Alcoa. It is now exploring a partnership with the government operation in China that controls the vast majority of that country’s 70,000 service stations.

The Alunergy battery could readily replace the internal combustion engine and gas tank without a major redesign of today’s automobile, and the company is talking with a European carmaker about commercialization.

But Tzidon said Phinergy is more likely to see two initial applications for its refillable battery. A bus would be a particularly suitable start, and that is something the company is discussing in China. It also hopes to go to market with a mobile storage device, basically a portable generator, in 2018.

Several observers who have seen the Phinergy concept up close call it “promising,” though they say the company will have to prove out its business plan and ensure the chemistry works as promised before it can take the Alunergy battery from concept to commercial application.

(Cadillac unplugs the ELR but will get back in plug-in hybrid game next year. Click Here for more.)