Just north of the Alabama border, a 16-mile stretch of Interstate 85 has become an infrastructural experiment that could transform the way highways across the country are designed, engineered and built in the years ahead.

Known as “The Ray,” and named after Ray C. Anderson, an environmentally minded Georgia industrialist, the experimental roadway introduces a variety of services and features designed to encourage both safer and greener driving. That include solar panels built right into the roadway. The project also uses recycled materials, including ground-up tires, to make the pavement itself more durable.

“On 16 miles of interstate in Georgia, we’re innovating the highway corridor from the ground up, creating a living lab that tests and proves what’s possible for roadway ecosystems across the globe,” organizers said when the project was first dedicated two years ago.

As soon as a driver heading north on I-85 crosses the border into Georgia they’ll get an indication something is different about the Ray. At the state’s welcome station, several key concepts have already been installed in the constantly updated project.

That includes a British-designed system called WheelWright that automatically measures a vehicle’s tire pressure. Drivers simply drive onto the system and seconds later they can either get a written read-out for each wheel or have the results sent to their smartphones. Improperly inflated tires can result in bad fuel economy – and are a major contributor to crashes.

The welcome center also features a large photovoltaic array used to power a battery-car charging station that travelers riding in electric vehicles can tap into.

And the Ray’s first stop also features a short stretch of pavement unlike anything ever used on a major highway before. Developed as part of a project pairing the French National Institute for Solar Energy, along with Colas, one of the world’s largest road construction companies, it replaces conventional asphalt and concrete with “Wattway,” a glassy brick with built-in solar cells.

Several companies are now working on similar technology, including a small, Idaho-based start-up, Solar Roadways.

(Missouri adding solar pavement blocks along stretch of old Route 66. Click Here for more.)

For the moment, the 538 square-foot Wattway system is being used to power the welcome center, but the team managing the Ray have more ambitious goals in mind if they can expand the system. The energy could be used in a variety of ways, powering highway lighting and signage, standard electric charging stations, or even an inductive charging system that The Ray plans to install. The idea would be to allow vehicles with wireless chargers – much like those now used with smartphones – to drive along, drawing power from the roadway itself, rather than using up what’s stored in their batteries.

The automobile takes a heavy toll on the environment. According to the management team, over 5 million tons of CO2 are emitted along the 16-mile stretch each year, something they hope to mitigate by adding more solar technology, including arrays in The Ray’s median, over the coming years. The plan also addresses solid and liquid pollution.

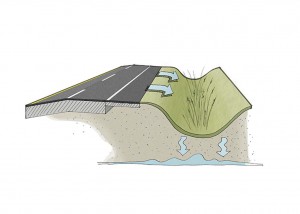

Landscaped drainage ditches, dubbed bioswales, are being set up along the roadway using vegetation that can absorb pollutants, rather than allow them to enter the groundwater system. A similar concept is being used at Ford’s massive Rouge assembly complex near Detroit to absorb oil and other run-off from the facility’s parking lots and roadways.

(New advanced driver technology could cause, not always prevent, crashes. Click Here for more on that breaking news.)

The Ray will add "bioswales" along its right-of-way to filter out pollutants, like oil, rather than let them enter local groundwater.

The goal is to continue adding new features along The Ray’s right-of-way. A new solar farm is being installed at around 14 miles north of the state border a new solar farm. Capable of generating a megawatt of energy, it is part of a joint project with the local power company.

The Ray may also get specially designed road barriers that will not only help reduce noise for surrounding communities but also collect solar energy.

While some of the ideas being incorporated into The Ray could be costly – using old rubber in pavement is about 15% more expensive than conventional asphalt – the management team contends that the overall cost-benefit equation should be considered in infrastructure projects. It may prove cheaper, in the long run, for one thing, if they can double the life of a stretch of roadway using rubberized pavement. Air and water pollution also have to be factored into highway costs, they argue.

Envisioned as a living laboratory, The Ray will let transportation planners move beyond theory and actually see whether their latest ideas can result in safer and more sustainable roadways.

(Trump rollback of fuel economy standards could cost billions. Click Here for the analysis.)