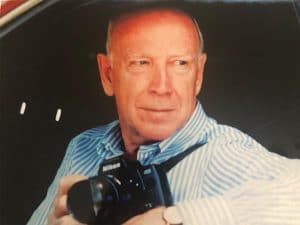

Jim Dunne was automotive journalism’s first spy photographer, often using guile and daring to get shots.

The morning meetings dragged on and it was finally time for the contingent of journalists invited to the General Motors Technical Center to sit down for lunch. But Jim Dunne had another plan in mind. He quietly fell behind the group, ducked into a restroom and slipped into the lab coat he had been hiding, complete with pocket protector.

He confidently strode back out and made his way to the Oldsmobile design studio, where he knew work was wrapping up on the marque’s next sedan.

Pulling out the pencil-sized Minox camera that was long a tool of the spy trade, Dunne quickly snapped off a series of pictures. Suddenly, a head popped up from inside the car, a senior Oldsmobile executive.

“Busted,” Dunne later recalled thinking. Then, another head popped up – the executive’s secretary. The two men locked gazes for a moment, a wordless deal having been made. Then, with a smile, Dunne walked back out with his catch, “spy shots” that would earn him a healthy payday.

While his weapon of choice was a camera, rather than 007’s Walther PPK pistol, Leo James Dunne was a legendary spy in his own right, the dean of photographers who chase a unique type of secret: new vehicles yet to be publicly revealed and, in many cases, even confirmed by their manufacturers. Dunne, who turned 87 last December, passed away Tuesday after a short battle with cancer.

“He was the father of spy photography, a pioneer of automotive journalism,” said Michelle Krebs, a long-time colleague and friend, after hearing word of Dunne’s death.

The Detroit native got into the “spy” business almost by accident, he once recalled during an interview for a profile story. He had found an old camera and used it to snap a picture of a partially camouflaged Corvair that a number of publications were trying to write about.

Though he had been reporting on the car business for some time, spy photography quickly became both his passion and a major source of additional income, since the magazine he worked for allowed him to sell his finds to other outlets that weren’t direct competitors.

With his work showing up in all the major automotive enthusiast magazines, as well as a number of mainstream outlets, “It put my kids through college,” he liked to recall.

Though Dunne officially retired a decade ago, he couldn’t resist occasionally picking up his latest camera, a Nikon digital SLR. TheDetroitBureau.com last published two of his finds – partially camouflaged versions of the soon-to-debut Ford Edge and Lincoln Nautilus – in August last year.

Months later, he discovered that he had contracted a rare and aggressive form of cancer that failed to respond to treatment. It was a shock to the few friends he revealed his illness to. Indeed, it was only in his final months that Dunne began to look anywhere near his nearly nine decades. While no fanatic, he long had tried to practice a healthy lifestyle, eating well, rarely drinking, and playing tennis until the disease had made his legs too heavy to move anymore.

Dunne was highly competitive, but had a close relationship with one of his primary competitors, Brenda Priddy.

In classic style, he approached the end of his life with surprisingly little anxiety, telling me earlier this month that “it was time,” and that he was “ready.”

With a surprisingly strong voice, considering he would go into hospice the following day, Dunne reminded me that he and the rest of us auto scribes “were lucky. We had privileges not many people get.” That included the chance to drive pretty much any car on the road and travel frequently around the world.

Along the way, Jim Dunne was always making new friends, among other things by walking over and asking, “Would you like me to read your palm?”

Jim Dunne “was a connector and a mentor,” recalled Krebs, who counts herself among the many automotive journalists he helped early in her career.

“He could be really helpful, but he could also be hyper-competitive,” added John McElroy, who often had Dunne on his TV show, Autoline:Detroit. “He was hyper-competitive and never wanted anyone muscling in on his gig,” added McElroy.

He recalled how Dunne once put grease all over the crook in a tree near the GM Proving Grounds in Milford, Michigan. It had been his favorite place to hide out and take pictures, but another spy had found the location and Dunne wasn’t going to share it.

“We all shared countless dinners with him while we were in Death Valley,” Brenda Priddy, another widely respected spy shooter recalled Tuesday, noting that despite their long friendship, “The only rule that I had was, if and when he asks you questions about the test cars, locations, etc., never answer him!”

Jim Dunne’s exploits were the stuff of legend – and he wasn’t afraid of burnishing his own stories. One of the most famous centered around his unexpected coup, landing a sliver of undeveloped property that jutted into the Chrysler Proving Grounds near Phoenix, Arizona. He simply could sit there and snap shots as the automaker’s latest products rolled by — until it caught wise and blocked the view from Dunne’s prying lens.

Eventually, he sold the land, which he bought for just $24,000, to a developer for 20 times that price – donating much of the proceeds to his sister’s convent.

“He was one of a kind and an inspiration to me and many others,” said Nick Twork, a public relations executive who started out as a teenage spy photographer working with Dunne.

There was little artifice to Jim Dunne. He defined the digital term WYSIWYG, or “what-you-see-is-what-you-get.” He was a great friend to those he respected.

He had little tolerance for those he didn’t. And, as Todd Lassa wrote in Automobile Magazine, “Jim’s instant-on BS detector” went on high when dealing with industry officials “whenever (their) answer was vague, or a dodge.”

There are plenty of solid reporters and proficient photographers covering the auto industry, and Jim’s work was certainly some of the best in both categories. But it was his unique style, drive and presence that will ensure that his stories remain the stuff of legend for years to come.

Paul, one of the best things you’ve ever written.

Thank you, Richard!