Two-tone paint was all the rage in American cars just before we got into World War II, and again in the Fifties. Indeed, it was the hallmark of the celebrated ’55 to ’57 models.

But fads come and go.

Today two-tones could be a route to resurgent demand for Detroit’s cars, a response to what I see as the boring sameness of both domestic and import sedans and the anemic earth tones and somber silver/gray/black paint schemes common to Euro cars and copied by Asians and Americans alike.

Actually, in the last few years two-tone has had an unheralded return of sorts at the edges of the marketplace. A car-knowledgeable PR exec for a Detroit automaker opines that the BMW Mini may have started it.

Two-tone has come and gone in recent years as a $295 option on Mercury Grand Marquis.

Today, in addition to the Mini, Ford’s Flex and F-series trucks, Dodge trucks, Chrysler PT Cruisers and Toyota FJ offer two-tone paint schemes in one way or another-either as a regular production option or as standard on a special model.

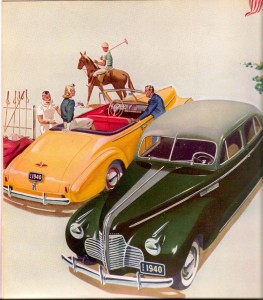

In the faulty memory of my childhood, I always thought it was the 1940 Buick torpedo sedans that pioneered two-tone, but some cold research showed Chrysler introduced it on some limited-production (fewer than 3,500) “New York Specials” produced on the Imperial chassis in 1938. The following model year, these Specials morphed into the long-lasting New Yorker series.

On the whole, though, my memory was right. Buick’s largest selling model for 1940 was the new Series 50 Super, 95,875 produced, all on the “four-window” torpedo Fisher “C” body design adapted from the pace-setting 1938 Cadillac 60-S Fleetwood sedan.

Among other things, the body style was noteworthy for having concealed hinges for the doors and front-hinged rear doors, unlike the rear-hinged “suicide doors” of almost all other sedans of the era. The torpedo C body was also offered for some Cadillac sedans, Oldsmobile Model 90 and a new upper series for Pontiac Eights.

My memory-and every photo of those cars I’ve uncovered-indicates that GM’s 1940 torpedo bodies all came standard with two-tone paint. (If I’m mistaken, doubtless TDB’s eagle-eyed viewers will let me know.) GM’s topcoat scheme featured either a light-colored roof over darker bottom, or vice versa. Buicks, and perhaps others, had the contrasting color stripe also running from the cowl to the front hood lip alongside the centered chrome strip or wind-split ridge in the hood sheet metal.

For 1940, Chrysler also brought back a two-tone option for all Chryslers, adding the paint offering for DeSoto (and possibly Dodge models) and extended the choice to Plymouth for 1941. Everyone but Ford climbed on the two-tone bandwagon for 1941 models, with the option costing a mere $10 on an $840 Plymouth P-12 Special Deluxe four-door sedan.

After the war, two-tone seemed to go away except for a handful of GM cars, but then became popular again with GM’s introduction of B-pillarless “hardtop” bodies introduced for 1949 models. White or black paint over the steel tops mimicked the canvas of true “drop- tops.” Other American carmakers fell in step with hardtops and the nearly obligatory contrasting roof colors. But soon, the color scheme options became reversed.

For example, my first new car was a 1955 Plymouth Savoy (mid-series) coupe with dark green top and a pastel green below. And by that time, a huge majority of new cars featured two-tone paint schemes, including some wild pastels and other happy colors. Also for 1955, Dodge and Packard came forth with tri-color schemes.

Most 1955 models of all makes had side-mounted bright-metal strips or spears, which provided a clear separation line between contrasting paint colors, now reaching below the previous top-only scheme. The results obviously appealed to the car-buying public and no doubt contributing to the boom year of 1955.

Two-tone paint faded, so to speak, in the 1960s but by the end of the decade began to be succeeded with faux convertible tops of vinyl, even padded vinyl, glued right over the steel tops of every body type but station wagons. Part of the eye appeal of this feature was the disappearance from the marketplace of real convertibles. Then in the 90s, contrasting color plastic lower body-clad parts became popular, especially on SUVs like the Ford Explorer Eddie Bauer model.

Dodge truck also has picked up on these lower-body contrasting paint scheme in lieu of plastic cladding.

Six years ago, Ford tentatively put its toe into the two-tone color schemes with an option on truck models only, paint in effect replacing plastic cladding, in other words around the bottom of truck sheet metal rather than the roof. As TBD colleague Paul Eisenstein wrote at the time, the Ford truck paint jobs resulted from a new technique jointly developed by DuPont and Ford called “wet on wet” or WOW. Dodge truck also has picked up on these lower-body contrasting paint scheme in lieu of plastic cladding.

Indeed, color paints made their way into automotive mass-production in the mid-1920s when DuPont and GM introduced Duco fast-drying paints. Before that, Old Henry, then producing more than half America’s cars, offered only black because it dried faster-but still took two or three days of “no-touch.” Duco cut that down to a reasonable few hours with more durable and color-friendly pigments to boot. Today, WOW allows painting one coating on another with virtually no wait, wet paint on wet paint with no bleed-through, the kind of process mass production loves.

Without fanfare Ford began offering two-tone, white, black or silver roofs as a $395 option on the Flex.

Without fanfare Ford began offering two-tone, white, black or silver roofs as a $395 option on the Flex at its 2008 introduction. Just eyeballing Ford dealer lots, it is apparent the option is quite popular, despite the fact Mercury dropped it for the Grand Marquis because of a low “take rate,” say 5% to 7%, about the time sister Ford introduced it on Flex.

So far the option has not spread further to conventional American passenger cars, except to some special models of the Chrysler PT Cruiser. The Toyota FJ, an SUV, is thought to copycat Land Rovers with sun-reflecting white tops for tropical climates.

I had the opportunity to ask Ford’s head of global design, J Mays, about the two-tone offering on Flex. Was this a harbinger of a resurgence of two-tone on cars? He said the Flex was a retro look at the 1939 Ford “woody” station wagon, because of both Flex’s contrasting color top option and the “side grooves” in the sheet metal and tailgate.

The side-grooved tailgate also is a new feature of the 2010 Ford F-series. I’m glad industry designers are glancing in their rear-view mirrors for inspiration, but personally I think when viewed from the rear the Flex more closely resembles my first Ford product, a used 1954 Ford Ranch Wagon.

I hope our industry designers reconsider contrasting roof colors for the otherwise look-alike, boring four-door sedans that constitute the majority of passenger cars these days. Mays suggested today’s sedan designs generally don’t offer the clear demarcations between greenhouses and lower bodies of the historical models like GM’s 1940 torpedo bodies that make two-toning easy. But I think two-toning could be an opportunity to put new life into old bodies in the third or fourth year of their cycles. Lines of demarcation didn’t stop Chrysler from two-toning its cars in 1940.

Further, I believe Detroit makers have an advantage over mass- production import brands when it comes to two-toning. Two-toning is nostalgic for historic American cars. And North American factories, still predominant despite import brand inroads, can more quickly respond to consumer fads than those that have to criss-cross ocean, language and cultural barriers.

Ford’s base $29,700 Flex with the $395 optional two-tone paint compares with a 1941 Plymouth’s inflation-adjusted $12,278 original price with $146 two-tone application. Of course, the vehicles aren’t comparable, the Flex having accumulated much more standard equipment and features in the nearly 70 years passed. But is today’s paint more than twice as good? Cultural standards have changed and people are more willing to pay premium prices for perceived value, and Flex’s contrasting roofs are clearly appealing.

C’mon, you designers, bring back more colorful two-tones. Banish the banal.

Can tailfins be far behind?

Tailfins? I think not. While two-tone paint is inexpensive to create and apply, new rear-quarter panels with fins probably would need hundreds of millions of dollars for design, test, tools, training and spare parts inventory–not to mention the interest charged by Wall Street sharks for the debt incurred. Besides, the greenies would see fins as wasteful and make them socially undesirable.

But a case could be made for a return to “pretty” colors like the light blue on my ’65 Comet convertible. I make take that cause on for a future column.

Domestic automakers have kind of dipped their toes into retro themed designs in recent years. Ford has done the Mustang and the GT. Chrysler has done the PT Cruiser, Prowler, and Challenger. GM has done the Camaro and whatever they call that Chevy PT Cruiser clone thing. Even foreign makers have done it. The VW New Beetle and BMW Mini come to mind. In a lot of cases, these cars have generated more public interest than any of the boring lookalike sedans that they all make.

But what if they really gave it a go? Think of some of the classic Detroit designs that could be reborn on top of modern automotive platforms. A new ’57 Chevy. A new late 1950s Cadillac with all those fins and chrome, in pink and baby blue! A new version of my personal dream car: a 1961 Lincoln Continental convertible with suicide doors. And that’s just scratching the surface.

As far as cost, well all car designs cost money to produce. And yes, America has forgotten how to make complex sheet metal shapes. On the other hand, we’ve got lots of know how in making complex shapes out of cheap composites.

Everyone says Detroit needs to figure out how to get the interest of the cool kids who live on the coasts if they want to survive. News flash, Detroit: mid century modern design (1950s-1960s) in architecture, furniture, clothing, and alcoholic beverages is all the rage with this crowd these days. They look for old cars from that period to drive. Camaros, Mustangs, and Challengers may appeal to the midwestern mullet haired set but not west coast hipsters. Tailfins, on the other hand, do.