The Solar Roadways blocks are also pressure sensitive and could light up to highlight a large animal or pedestrian crossing the road.

One of the most famous roads from America’s past could soon become the highway of the future, at least if a project launched by the Missouri Department of Transportation pans out.

MoDOT, as its locally known, plans to become the first public highway department to test out a new type of pavement that not only replaces conventional concrete and asphalt but which also can generate electricity through built in solar panels. The technology was developed by an Idaho-based start-up called Solar Roadways.

“If the solar roadway concept proves to be feasible it creates electricity and could be the first road in history to ever pay for itself,” said Tom Blair, the team leader on Missouri’s Road to Tomorrow initiative, which was created two years ago to find ways to increase the state’s investment in its roadway infrastructure without raising taxes.

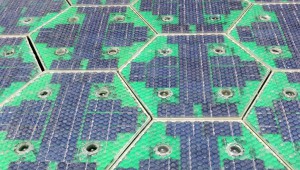

Solar Roadways, founded by husband-and-wife entrepreneurs Julie and Scott Brusaw, has developed a hexagonal block of about 4.4 square feet made of tempered glass strong enough, they claim, to stand up to even the heaviest truck traffic. The glass blocks have a mu, or traction, similar to that of conventional asphalt.

But they each contain solar cells capable of generating up to 44 watts of current, “entirely dependent on the sunshine they receive,” explained Julie Brusaw by e-mail.

The blocks also have built-in LED lights that can display lane markings bright enough to be seen in daylight – and which can be reprogrammed if there’s a need to shift lanes, for example. The electric current can be diverted into the grid or power heating elements that, during winter, would minimize snow and ice accumulation.

While final details are still in the works, MoDOT plans to have the first Solar Roadway blocks in place “before the first snow falls this year,” said project leader Blair. Initially, the glass pavement will be used to replace most of the sidewalks at the Route 66 Welcome Center and Museum in Conway, Missouri. It’s located where the original Mother Road, as the highway was known, has been supplanted by Interstate-44.

(Long decommissioned Rt 66 lives on. Click Here to motor west on the Mother Road.)

The energy the blocks create will be used to supplement power the center now gets off the grid, a process that will let MoDOT “directly measure what the payback would be in the real world,” said Blair.

The next step will be to use the Solar Roadway blocks to replace the pavement at the welcome center and perhaps install them on a stretch of Historic Route 66 nearby, added Blair, noting that rather than tapping the state’s already over-stretched highway budget, the goal will be to apply for grants and seek additional funds through crowdsourcing.

The Brusaw’s have used a similar approach to fund the development of the solar pavement, with the company receiving a series of grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation while also raising several million more through crowdsourcing.

(Which company claims to be leading in automotive innovation? Click Here to find out.)

The initial deployment at the Route 66 Welcome Center will cost about $100,000, according to Blair. The Brusaws declined to discuss the actual cost of each block, Julie cautioning her e-mail that, “This is just a pilot project, so mass production is not being used yet. If all goes well with the pilots, we hope to gear up for it in the next few months.”

That could sharply drive down the cost, though the solar road blocks would still cost more than conventional concrete or asphalt. But the Road to Tomorrow initiative has concluded that if the technology works as promised, it would not only quite literally generate money by being wired into the grid, but also save money on highway maintenance. If the blocks can melt snow and ice, said Blair, they’d need to be plowed and salted less often, for one thing.

The MoDOT project is just one of several pilot programs Solar Roadways hopes to participate in. It expects to soon install some of its blocks on public roads near its headquarters in Sandpoint, Idaho. And it is working on others, the founders claim.

There are 29 mil square miles of paved roads in the US; each could potentially produce over 270 megawatts of power.

Noting that there are about 29,000 square miles of paved roads in the U.S., Scott Brusaw said he believes a significant chunk of the nation’s growing energy demands could eventually be generated by switching to solar blocks. For those good at math, there are about 27.8 million square feet per square mile of road — equal to 6.32 million of the blocks. At 44 watts, one square mile would be able to generate a maximum of about 278 megawatts — at least, theoretically. By comparison, U.S. nuclear plants produce anywhere from 479 megawatts to 3.8 gigawatts of power over a 24 hour period, according to the Energy Information Administration.

(Plug-based car sales set for explosive growth. Click Here for the latest.)