World War III is taking place in my backyard. The sound of machine gun fire pierces the air, backed by the diesel growl of Humvees and Oshkoshes.

Hollywood has come to Detroit again.

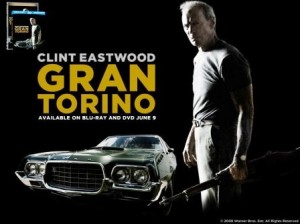

Last year, it was Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino, a story originally set in Minneapolis about Southeastern Asian immigrant street gangs and a crusty vet. My contribution was that I had sold a bunch of books on Detroit and Michigan history to a nearby used book store, which the prop manager for the movie crew snatched up to fill the Clint character’s bookshelves for authenticity.

This week, it is a remake of Red Dawn, the 1984 teen thriller about kids fighting Cuban invaders in the mountain wilds of Colorado. As to how this story line was morphed to a middle-class suburb of Detroit, we will just to wait and see the finished product. Anyway, the local cops have blocked the streets and sidewalks around my neighborhood to prevent the curious from appearing in the background of costly scenes, sort of like the contrails in the sky we used to notice in horse operas, otherwise known as Westerns.

The arrival of Hollywood in Detroit results from the state of Michigan giving movie production companies huge tax breaks making it economically feasible to produce major films here for the silver screen. At a minimum, a few crumbs fall off the table for the local populace. The movie company seems to be doing everything right. A police sergeant told me it was gravy for the cops on overtime with the city police budget not being scavenged to help the movie folks.

Of course, the populace of California and New York City are used to the Hollywood treatment — maybe even Washington, Chicago, Miami and Las Vegas, other favorite movie on-location locales. But gritty old Detroit? Only if a director wanted to show urban squalor and abandoned factories. Now that’s changed, and for the good.

In fact, before television, Detroit used to be a major site for production of motion picture films made by firms like the Jam Handy organization. These were training and promotional films underwritten by automakers; theater houses welcomed the promos to fit between the double features of the good old days.

Further, for decades Detroit’s automakers had close ties to Hollywood, through their “studio car programs” that places the car brands into feature films or TV shows. Because the cars and trucks provided free to the studios traditionally were used as private vehicles by studio execs and even actors when not being part of a production, and that class now leans to Lexi, Beamers and Benzes, Detroit’s hold on this costly niche market has been weakened in recent years.

I suppose my attraction to pre-war Buicks was fueled by seeing so many of them in my favorite movies of the period, thanks to Buick’s promotional efforts with the studios. One of my treasured wall pix is a publicity shot of a ’40 Buick touring car in the next-to-last scene of Casablanca, in which Captain Renault utters the famous line, “Major Strasser has been shot. Round up the usual suspects,” while Bogey’s Rick lurks nearby with a still-smoking .32 Colt automatic. The odd thing is the Buick has bullet holes in the windshield, something that never happened in the actual film screened. As I recall reading, right up to the end of production the movie’s climax was unsettled and a couple of versions were filmed. The one creating Buick’s bullet holes ended up on the cutting room floor.

However, the biggest connection between Hollywood and Detroit is that both industries invest years and enormous amounts of money — millions — producing, respectively, a new movie or a new model car, with no real assurance whether it will be successful or not.

In Detroit, the regret for a flop is expressed as, “The dogs didn’t like the dogfood.” I don’t know what the Hollywood equivalent is. Maybe someone will tell me.

At least a movie flop in the U.S. can be readily peddled overseas. Not so Detroit’s iron.