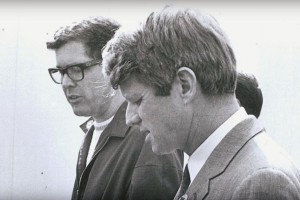

Former adviser to Robert Kennedy and UAW organizer Paul Schrade, who's impact on the union seems to have been overlooked.

When John F. Kennedy first approached Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers at the 1956 Democratic Party Convention, hoping to win his support for the Vice Presidency, Paul Schrade, as one of UAW President’s top aides, observed the meeting.

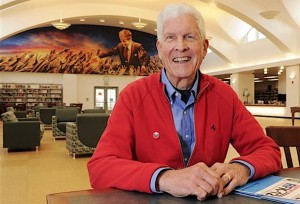

However, the vital role of Schrade, who is now 93 and still an activist, in UAW history has been largely overlooked by union during past four decades as the UAW has struggled to maintain its influence both at the bargaining table and in politics.

But Reuther, who had an eye for talent, according to historian and biographer Nelson Lichtenstein, had recruited Schrade to serve on his staff because the “bright young radical” union activist had already made his mark among UAW’s local officers in Southern California’s booming aerospace industry.

After his stint in Detroit and with Reuther’s backing, Schrade was elected to the UAW’s top executive board where he served as director of the union’s western region. He also served as the UAW and Reuther’s unofficial ambassador to the farm workers and anti-war movement on the West Coast. In 1968, he was shot while walking next to Robert F. Kennedy, who had just won California’s all-important Presidential Primary, through the kitchen of the Los Angeles Ambassador Hotel 50 years this week.

(UAW’s Williams supports Trump’s tariff proposal. Click Here for the story.)

The coalitions Schrade, as the UAW’s regional director, built in California were not only pivotal in Kennedy’s victory in 1968, but also in the earlier Indiana primary where Kennedy had succeeded in building the kind alliance between blue-collar workers and minority groups that Democrats have talked about building to oppose Donald Trump.

“I remember watching the votes come in from the barrio in East LA and I knew we had won,” said Schrade, who also had been arguing for weeks with Reuther over the support he had provided Kennedy. At the time, Reuther was reluctant to break with President Lyndon Johnson.

Ultimately, the argument about the Vietnam War, which Schrade passionately opposed because as he told Reuther the “sons of our members were being killed,” alienated other UAW officers, notably Reuther’s successor Leonard Woodcock, cost Schrade his seat on the union executive board in 1972.

Schrade returned to work in a blue-collar job at North American Rockwell, the builder of the space shuttle, and finally retired in 1980s.

The United Auto Workers often extols for contributions of key figures have made to organized labor, civil rights and social justice in general. Among those on the list singled out for praise are figures such Reuther, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela and the Kennedys.

But throughout the years, Schrade’s role in paving the way for the alliances beyond the industrial Midwest has been largely ignored except by historians such as Lichtenstein, the author of the most author of the most authoritative biography of Reuther and his era, “The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit.”

“I’ve never been invited to a UAW convention,” said Schrade.

During his tenure on the executive board, Schrade developed close ties to the Civil Rights movement and became one of the leaders of the anti-war movement on the West Coast that grew in opposition to Vietnam War.

He helped organize community organizations in Watts and East Los Angeles and reached out to support the United Farm Workers, a force that ultimately re-shaped politics and culture in the State of California.

During the late 1980s, he served as an unofficial adviser to Jerry Tucker, the union executive board member, who led the New Directions Movement.

Tucker, who died in 2012, was a leader of what “Labor Notes” described as the “troublemaking wing” of the UAW, had warned repeatedly the joint programs the union launched in the 1980s to nurture what was described as labor management’s cooperation could and would water down the UAW’s identity and corrupt the union — a prediction borne out by the ongoing federal investigation of joint funds at Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V.

Schrade, who at 93 is still very active and recently consulted on documentary about Robert Kennedy for Netflix, is also still willing to offer advice to his UAW colleagues.

“They ought to take money out of the strike fund and use it to organize in the in the South. “There are a lot things happening in the African-American community in the South if you look at Alabama and at Texas,” Schrade said in a telephone interview last week. The union has no choice but to keep organizing and building alliances if it wants to stay relevant.

Paul Schrade maintains that Sirhan Sirhan could not have shot Robert Kennedy and is pushing for an investigation.

Schrade also remains close to the Kennedy family, having met both JFK and RFK during the 1956 convention when the Kennedys sought Reuther’s support for Democratic vice-presidential nomination on a ticket with Adlai Stevenson.

He recalled during one interview that Reuther told JFK that had to do “more for labor.” History suggests that Kennedy followed Reuther’s advice as his record became decidedly more friendly toward labor over the next four years in the run up to his nomination and run for President in 1960.

Reuther also developed serious reservations about the Vietnam, but he also wanted Johnson’s support in the union’s negotiations in the auto and aerospace industries, Schrade recalled.

In 1968, the UAW’s executive board was divided about one third supported Kennedy, another third supported Johnson and one followed were waiting for Reuther to make a decision.

Schrade also does not believe that Sirhan Sirhan killed Robert Kennedy.

(Click Here to see more about the UAW struggling with credibility in the wake of the FCA-UAW scandal.)

“Sirhan’s first shot missed Kennedy. His second hit me,” said Schrade during the telephone interview. “I have two holes in my head. Fortunately I still have hair,” added Schrade.

Sirhan was then grabbed by one Kennedy’s escorts who slammed him into a stainless-steel tables in the kitchen. But the Sirhan’s pistol continued to fire, hitting four other people before he stopped shooting.

Schrade is actively lobbying for the parole of Sirhan Sirhan, whom he doesn't believe shot Bobby Kennedy.

“He was out of position and out of bullets,” noted Schrade, noting an autopsy said he was shot from behind, indicating clearly the presence of a second gunman.

“I consider myself a public prosecutor. I’m not interested in conspiracy theories. I’m just looking at the evidence,” said Schrade, who notes the Kennedy family also has now spoken out publicly about the existence of a second gunman. “The case should be re-opened. I want to see justice for the Kennedy family.

“It was horrible, horrible. Bob was a great friend,” said Schrade, who has described RFK as organized labor’s ally and “as the best candidate we ever had.”

(To see more about the UAW membership increase in 2017, Click Here.)

“It was a great loss,” he said. “It’s got to be investigated. We’ve got fake history now. We’ve got to get it right,” he said.