The UAW has been equally devastated by Detroit’s misfortunes, but in ways that most elitist "opinionators" don’t understand.

Once upon a time half a century ago, covering the Labor Beat was a big deal, both nationally and in Detroit, home of both the United Auto Workers and the Teamsters unions, with their respective leaders, Walter Reuther and Jimmy Hoffa, in the news practically every day. Major media, and TV did not count in those days, had dedicated slots for “labor writers” or “labor editors.” I was one of them, as part of my duties covering the auto industry.

At the time, the UAW was more than just autoworkers. Its reach included farm equipment workers and the aircraft industry (dating from World War II).They were the intellectual leaders of America’s union movement. Moreover, in truth, Reuther’s UAW invented many of the benefits that the middle class now counts as its birthright.

After Reuther was killed in a plane crash in Northern Michigan and his team of old-line incorruptible Socialists began to age out, the Union lost its fervor. Gone in my opinion was its vision and its mission — due to circumstances beyond its control, namely Detroit’s declining share of the U.S. auto market and the transplants that the UAW could not organize.

Some union members and local leaders went un-chastised by Solidarity House (UAW Headquarters in Detroit) when they got involved in disability scams with crooked lawyers. The UAW vigorously defended a Michigan metal stamping plant employee caught urinating on a stack of newly pressed steel panels. Likewise, a bunch of UAW workers left an Ohio auto plant for a bar across the street, where they got into a big enough fight for the cops to be called in. On investigation, it turned out they were all checked in at the plant, supposedly earning their nice hourly wages and benefits, and once again, the union supported them.

A telltale book, 1991’s Rivethead: Tales From the Assembly Line, about workers in Flint auto plants being drugged out or drunk on the job, deliberately sabotaging their products, was brushed off by UAW officials.

The UAW did become more concerned about the issue in recent years, especially in terms of drug and alcohol issues, though as likely as not, when there were arrests for in-plant dealing, it was the union that would call for treatment instead of dismissal.

Meanwhile, this situation crossed both sides of the border, before and after what was the truly international UAW lost half of its operations to the newly formed Canadian Auto Workers, two decades ago.

We had a very candid conversation, last year, during an event marking the Chrysler minivan’s 25th anniversary, with a union manager who was frank about a plant known to both labor and management as “the zoo.” There was drug dealing, even more widespread usage, often up on the roof, until both sides acknowledged the problem was going to kill them both, and they cracked down.

Ultimately, the domestic auto industry paid the price in quality reputation and non-competitive legacy costs versus imports and transplants. Arguably, both management and union — not to mention national policies permitting unequal competition from overseas– all share the blame.

That was then. This is now.

The UAW has been equally devastated by Detroit’s misfortunes, but in ways most journalists and elitist “opinionators” don’t understand. Sure, many UAW members, like non-union salaried and even executives, have been forced into early retirements or layoffs.

But that’s not the full impact to the UAW as an organization. For one thing, workers on layoff or in retirement no longer kick in two hours pay a month for dues that active members pay. For another, there is a literal army of what in-the-know auto experts call “pork choppers,” elected union representatives in plants, who have been lost to the union political power base with themselves either forced into returning (on a seniority basis) to the line or to the machine for actual production work, or retired like their flock. No longer can they spend their time and energy supporting union and Democratic Party activities while representing their workers in disputes as needed.

The other big impact on the union is that the UAW, according to the arrangements forced on bankrupt GM and Chrysler by Washington, now is an owner and in effect manager of two of the three Detroit auto companies.

No longer is it philosophically “us versus them,” labor versus managers or owners. While the union is hiring outside experts to run its agreed takeover of union member health and pension benefits, nevertheless it has a direct stake in the industry’s costs and therefore profits. This makes it much more difficult to maintain a philosophical position of opposition to management.

One way the UAW had sought to offset these challenges is to set about organizing employees in other areas than auto plants, especially college employees and even professionals at the Detroit Public Library. Indeed, sometimes they are competing against newly muscular public employee unions.

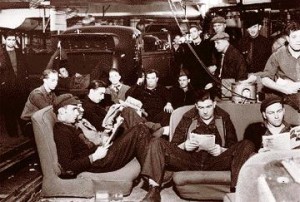

Union management is no longer that of the rough-and-tumble Sit-down Strike organizing days of the 1930s.

Of course, the union management is no longer that of the rough-and-tumble Sit-down Strike organizing days of the 1930s. UAW president Ron Gettlefinger is the first autoworker president with a college degree (Indiana University); two of the UAW’s other executive committee officers also have not only undergraduate degrees but law degrees as well. However, unlike auto company management, at every step up the ladder from the shop floor on, these union leaders are elected by their respective organization’s members.

Today, that puts them between a rock and a hard place, a situation not fully appreciated outside the industry. In internal union politics, the leadership knows that pork choppers represent a non-productive cost to American auto companies, but these are the same people who get out the vote in union elections, as well as local state and national ones. They know that rather than being in a 100% adversarial position versus the companies, they are now financial partners.

That’s not a concept entirely missed on past leaders, we admit. It became increasingly apparent to the recently deceased Doug Fraser, the brilliant but hard-fisted UAW president who helped Chrysler win its first government bailout nearly 30 years ago.

However, one of his top lieutenants, the late Don Ephlin, lost his bid to succeed Fraser, largely because he was seen as too close to the automakers. Instead, the UAW was taken over by traditionalists like Owen Bieber, who may have been increasingly aware of the dead-end path ahead, but who held to the hard line.

Still this might have succeeded, but for the fact that the union has failed to accomplish one of its most cherished — and some would say desperate — ambitions. Since Reuther, the UAW has sought to put all U.S.-based auto operations under its banner.

Discounting smaller, non-union suppliers, the real problem has been the so-called transplant assembly lines, which began opening in the mid-1980s, and which now produce roughly a third of the vehicles sold here. These offshore-owned assembly lines are non-union. Makers such as Nissan, Toyota, Hyundai or BMW typically open plants in southern states with anti-labor histories and even non-union laws on the books.

Though it has staged numerous organizing efforts and even forced a couple of elections, the UAW has failed to win representation rights at a single transplant — with the exception of a few facilities set up as “Big Three” joint ventures — one of which, the Toyota-GM operation, NUMMI, is now closing.

Quite aside from all of the above, my observation is that the autoworkers union, which I know best, has since the end of World War II filled a unique role in American society: the clubhouse. As such, local unions have replaced many of the traditional lodges, like the Elks or the Knights of one thing or another. Union members and retirees gather in their clubhouses, AKA local headquarters, to socialize or seek intervention or advice in their personal lives or disputes with local municipalities, where union influence is helpful. When an auto plant closes permanently, its local union as a bargaining unit shuts down also, but not the club.

How all this evolves under the new rules governing domestic auto industry operations remains to be seen.

What was once unthinkable has happened.

The future is unknown.

Relevant history, well told!

Retirees “never” kicked in two hours pay per month for Union dues. I don’t know where you got that one from.

Tater Salad — I think you misinterpreted what I wrote, and re-reading it, I can see why. I know perfectly well that active union members pay two hours pay per month as union dues, but those no longer active, whether on layoff or retired, do not. No doubt the sentence could have been clearer on this point, for which I apologize.

No big deal here. You mentioned Don Ephlin above and being too close to the company. As a former union official myself, one (and a big one) of the reason contracts escalated over the years was because management was was ripping off the “system” with huge bonus’s for salary members and perks. Starting in 1970 the Union started demanding the same. Management would not give up and the Union pushed back. The end result….2007. In the future I hope management keeps their bonus’s & perks under control and the Union “will” do the same.