General Motors, Tesla and the slew of other automakers bringing new EVs to market are going to face a new issue sometime soon: what to do with the old batteries?

Battery cars currently account for a small fraction of the vehicles being sold but that’s expected to accelerate rapidly in the coming decade as more products come to market and regulators around the world enact strict new emissions and fuel efficiency mandates. So, with an estimated 300 million electric vehicles on the road by 2030 that raises a significant challenge for the industry: what to do with used batteries at the end of their “first life?”

With an estimated 4 million electric vehicles coming off the road in 2030, the challenge will be to develop ways to either reuse or recycle their battery packs – something that could create a $10 billion market, according to a new study by the Boston Consulting Group.

“The last thing we want is to have batteries, the highest value components (in an EV) to wind up in landfills,” said Aakash Arora, a BCG managing partner and lead author of a study on developing a “circular economy” based around used vehicle batteries.

(Lucid Air to offer biggest battery pack of any EV — and the longest range.)

The Volvo XC40 Recharge Battery Package is just the first of what will be a variety of vehicles using batteries.

Today, about 32 million electrified vehicles are in use worldwide, the BCG study estimated, including 8 million plug-in hybrids and pure battery-electric vehicles, or PHEVs and BEVs. The rest are various types of conventional hybrids that don’t need to be plugged in. By the end of the decade, the consultancy forecast, the overall number will increase tenfold, with a growing emphasis on plug-based models using larger battery packs.

The good news, said Arora, is that the battery packs in the majority of those vehicles will have enough capacity left to find a “second life.” That could include a variety of applications, such as being used to power forklifts and other factory equipment, as well as for stationary applications such as backing up cell towers or load leveling electrical grids.

Grid systems are already gaining momentum, among other things, to fill in when solar arrays or wind generators are down.

“We should be able to create a good use,” said Arora.

About 4 million battery packs will come off the road in 2030, the study forecasts. That number will rapidly grew in the years behond as sales of electrified vehicles accelerates.

The BCG study anticipates that by 2030 as much as 30% of the high-voltage automotive batteries – typically lithium-ion – will find second life applications.

That figure could grow, said Nathan Niese, a BCG associate director, as lithium technology improves. Today, most batteries are expected to be near the end of their useful life by the time a vehicle is scrapped – if they last even that long. But, he noted, new chemistries and other breakthroughs could substantially extend the useful capacity of the batteries that will come to market over the next few years.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk, for one, has indicated his company expects the battery upgrades it’s now working on will allow them to last for as much as 1 million miles.

That would be particularly useful for high-use applications, such as taxi and ride-share fleets, as well as in the wave of new electric trucks soon to reach market, like the Tesla Semi.

(GM EV program charging ahead despite dynamic.)

Pulled out of a conventional passenger car, such long-life batteries could find significant second-life applications.

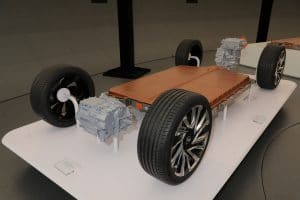

GM showed of its third-generation global electric vehicle platform with its Ultium battery technology.

But all batteries will, at some point, lose enough of their initial capacity to warrant being scrapped. The challenge is to develop methods that can cost effectively recycle their components, said Arora.

It helps, he noted, that some of the raw materials used for lithium-ion batteries are considered relatively precious commodities, notably cobalt but also including lithium and nickel.

With virgin supplies potentially running short as demand for battery technology grows, that will only encourage the development of effective recycling methods, according to BCG.

Right now, however, “there are a number of questions” as to how efficient battery recycling can be, said Niese. A case in point is Volkswagen AG, the German automaker that plans to have about 50 different all-electric models in production by mid-decade. Currently, only about half of the batteries in its vehicles are being recycled though, said Niese, “they have a roadmap to get it up to 90 to 95%” during the coming decade.

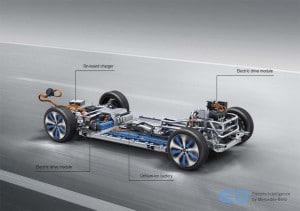

Hyundai and Kia will use Canoo’s EV skateboard to underpin an electric vehicle about the size of the Hyundai Accent.

Recycling programs are now most advanced in China, the country expected to have the largest market for battery cars going in the coming years, the BCG study indicates.

At that level, recyclers should be able to recover between $30 to $40 worth of raw materials for every kilowatt-hour, or about 30 to 40% of what General Motors expects to spend per kWh once its new Ultium technology goes into production at a new plant in Ohio next year.

That creates “a real business case to be profitable,” said Niese.

(GM, Tesla charging toward million-mile battery goal.)

But equally important, the study stressed, aggressive recycling should reduce the risk of shortages of some of the most critical materials needed to produce new lithium-ion batteries.

Some key unanswered questions:

How many batteries are in need of a future/recycling annually?

What does it cost to recover $30 to $40 worth of raw materials?

How many batteries are now being recycled?

How many batteries are currently used in other applications (fork lifts, …)?

What’s the danger of recycling a partially charged battery?

Jim, these are all good questions. Note some answers in the story, ie the estimate of 4 million vehicles coming off road in 2030. That would be 4 mil packs, though they didn’t have a specific number of battery cells. Recycling of batteries is relatively rare right now, but growing. China is, according to BCG, already at north of 90%. Elsewhere, the figure is substantially lower. The cost of recycling is a question that will likely depend on improving processes AND increasing scale, the study emphasized. Use in other applications is currently low as there aren’t many batteries yet coming off the road so it is more difficult to create products needing second-life batteries. Most programs right now appear to be tests and demos, including stationary uses. I cannot answer that latter question. I assume recyclers have ways of dealing with that issue just as they do with current 12V batteries and gas tanks.

Paul E.