While car enthusiasts, engineers, critics and regulators all rejoice today at the impressively higher safety belt wearing rates that have contributed importantly to lower rates of fatalities in crashes, the road here has been rough. Thirty-five years ago, and say 175,000 unnecessary deaths since, we as a nation had a proven preventative—but the public, the critics and above all Congress muffed it.

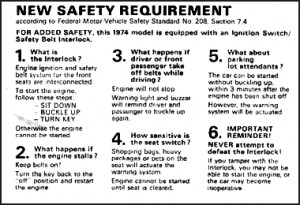

This seat-belt interlock somewhat crudely, prevented the car from being started unless all front-seat occupants buckled their safety belts first. With only a six-month lead-time, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) mandated the device for all 1974 model cars in the U.S.

The seatbelt interlock was, in my opinion, a good idea whose time simply had not come.

There’s a persistence mythology even today about automotive safety that says you’re better off if you’re “thrown out” of a car in a crash. This was disproved in the early 1950s by an Indiana State Policeman named Elmer Paul.

Sergeant Paul noticed that, in many fatal highway crashes, the vehicle really wasn’t badly damaged, yet the people were dead. Why?

He discovered that such fatalities inevitably resulted when occupants were ejected and crushed either by the vehicle rolling over them or by crashing themselves into a tree, pole, curb or whatever.

The laws of physics are irrevocable, stating that a body — human in this case — in motion continues in motion until stopped. You don’t get “thrown out,” you keep moving after the car stops impacting something else; you “stop” when you also impact something else, whether the instrument panel or, say, a tree.

Paul collected good statistics on Indiana “fatals” showing that ejection was the leading cause of fatal injuries. He got the attention of the National Safety Council, the Automobile Manufacturers Association and the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory that had specialized in aircraft safety during World War II but had little to keep busy in the post-war period.

This was when test-track simulated crashes began, using crash “dummies” as surrogates for people. Given the timeframe and cast of characters, no surprise that the main solution to the ejection problem came from aircraft — the seat belt.

Seat belts, of course, were invented to keep airplane pilots from falling out in aerial maneuvers and passengers from being bounced around. They’d been introduced, as I recall, as a “comfort” option in the stubby 1950 Nash Rambler.

Now Ford introduced — and promoted — a safety package in its 1956 models. The package included outboard front-seat lap belts, improved door latches, a deep-dish steering wheel and padded dash.

Only the first two items, of course, related to the ejection problem; the recessed steering wheel hub and padding were aimed at reducing injuries from impact of the occupants with the car interior. Padding had appeared before, on the 1948 Tucker prototypes and as standard equipment on 1949 Chryslers. The other domestic manufacturers quickly duplicated Ford’s package, especially the optional belts.

However, the Motoring Public couldn’t have cared less.

You heard, Race Car Drivers Don’t Wear Belts, Why Should I?

Sad, but true. As a journalist, I covered the ‘56 Daytona Speed Week, when it was still held on the beach and Florida State Highway 101. I believe only Bill Stroppe’s superbly prepared Mercurys had belts. Even in 1965, race drivers didn’t universally accept belts. I witnessed my one and only “fatal” at the Riverside track a few years later when a belt-avoiding driver had his head crushed on the A-pillar when his car hit a retaining wall.

You heard, If I Wear A Belt, I’ll Get Trapped

Variations included … in a fire, or when the cars goes into the water. There were so few of those cases, statistically speaking, that they weren’t worth worrying about. Urban myths die hard.

In the meantime, the national highway death toll continued to climb towards 50,000 annually (even though the rate declined). It became the auto industry’s first time at bat as a national whipping boy since the anti-trust hearings of the New Deal 20 years before. Critics demanded that the optional safety devices be made standard. In hindsight, if the industry had quickly agreed, many of the problems of public perception (“foot-dragging”) it has today could have been mitigated, if not avoided. But in those days, the big concern was anti-trust, and there was no legal way the industry could have sat down and agreed to any common product (and resulting price) change.

Individual states began introducing laws mandating favorite safety gadgets, whether useful or not. Detroit was almost grateful for passage of the National Highway Safety Act (in which the infamous GM hiring prostitutes in a failed attempt to discredit Ralph Nader was a catalyst) because it avoided the chaos of every state having different requirements.

Beginning with 1968 models, the resulting automotive safety standards mandated, among many other equipment and test requirements, lap belts for every seating position and shoulder belts for the outboard front occupants. The problem then was that there was no incentive to get people to fasten them.

About the same time supplier companies and auto manufacturers began experimenting with air bags to protect occupants from injuries impacting the car interior in head-on crashes. That’s right — air bags NEVER were intended to do anything about the leading cause of fatalities, ejection from the vehicle. ONLY THE LAP BELT can do that. However, the air bag appealed to the self-appointed safety “experts” in media and the Washington critic chorus (most of whom were lawyers) because it was a passive device, not requiring cooperation of drivers and occupants to be effective, unlike seat belts that had to be fastened.

Leaving aside the many concerns manufacturers had about costs and successful technical development of air bags as supplemental restraints, to make a real dent in the highway death toll, some way of getting people to “buckle up” still had to be devised. From its research, Detroit understood that even air bags required belts to “position” occupants for effective protection.

Despite all the hullabaloo about auto safety from Washington and the “safety Nazis,” as they were dubbed, and continuing attempts at education by many players, surveys showed only a relative handful used the newly-mandated installation of safety belts.

(It was analogous to smoking cigarettes, where everyone knew it was bad for you –“coffin nails” in my youth — but kept on doing it anyway. What the hell, we’re immortal. But times do change, and people do get smarter or perhaps just get scared into ceasing.)

From somewhere in the depths of Ford Engineering, or perhaps from a vendor hoping to get a lucrative supply contract, the concept of a seat-belt interlock arose in the early 1970s. Electronics were at best in their infancy, and mass-production product engineers viewed even electromechanical devices suspiciously. But experimentally, at least, the device worked.

Interlock Mechanics

There were two sensors involved, one in the seat and the other in the lap-belt retractor. A primitive logic device tracked a rigid sequence in which when a prescribed weight was detected on the seat, the lap belt had to be fully pulled out before an interlock to the ignition switch was released. Each seating position in the front had to cooperate in proper sequence, or the car wouldn’t start.

Ford ran a series of consumer tests with the devices mounted in test cars that showed an incredible increase in seat-belt usage. It could hardly have been otherwise. You couldn’t start the car unless you and every other front-seat occupant (when most cars had three-person bench seats) buckled up. Yes, you could unlatch it after you were started, but the research showed relatively few committed this redundant sin. The engineers took it to “Management” who took it to Ford President Lee Iacocca. Iacocca quickly grasped that the device could take some Washington heat off Detroit and, when it was spread among the motoring public, make a significant contribution to reducing highway carnage — by preventing ejections.

When Ford presented the idea to Washington, unfortunately, the then still relatively inexperienced NHTSA staff bought the concept and without allowing time for further development and experiment, mandated it for 1974 models due to be introduced only a few months later. Manufacturers and suppliers “crashed” to meet the requirement. Ford’s competitors no doubt ground their teeth at the folly.

Unfortunately, it was all too much, much too soon.

The unseemly haste of dictating a huge change in American motorists’ habits prevented a reasonable, normal development period to “de-bug” the gadgets. The result was that grandmas, grocery bags and guard dogs alike triggered the no-start unless the belts for the front seats they occupied were fastened first. Plus, people rejected the Big Brother attitude of forcing them to buckle up before they’d bought into the notion. Back then, only 10 to 15% of occupants buckled up; today it’s up to nearly 100% in some American jurisdictions for front seats.

A huge outcry quickly arose. Frustrated and indignant citizens bombarded Congress to complain about the devices, and our representatives quickly passed a law outlawing the interlocks. The safety critics quietly chuckled and hastened their campaign for mandatory bags, even though the bags, to state it one more time, didn’t prevent ejections.

True, automotive safety was set back for years, and untold numbers of victims died unnecessarily.

I base my 175,000 fatalities estimate on a savings of 5,000 lives a year for 35 years. Whether that is too high or too low, know one really knows, but it certainly is in the many tens of thousands.

Personally, while I believed in the interlock devices for their undoubted safety merit, I too experienced problems. Our family car that fall was a new 1974 Ford Gran Torino Squire station wagon. Our house had a 75-foot-long, curving driveway and to get out, you had to back up leaning out the driver’s door. With the lap/shoulder belt fastened, you couldn’t lean out. As a faithful seat-belt user from the very first (that is, when I bought my first new car after 1956, a 1962 Ford Falcon), my pattern was to back out, then fasten the belt before driving off.

The seat-belt interlock wouldn’t let me do that. The only way I could start the car was to fasten the belt, hit the ignition switch, then — cursing — unfasten the belt so I could lean out to back up, and once more fasten the belt when I was ready to hit the road. My wife thought my employer Ford was simply insane for dreaming it up in the first place.

Well, over time in the 1980s and ‘90s bags were further developed and aimed at, first, limited production in selected models and than mandated for both driver and right front passenger.

However, NHTSA dictated that the performance standard for the bags had to be a worst-case assumption that the occupant would be a 165-pound unbelted male. For whatever reasons, they chose to overlook research that showed the incredible increase in safety belt usage along with long-standing industry concerns about dangers of air bag deployment to the small and the frail.

As a result of a new uproar about child deaths in air bag deployments in the 1990s, NHTSA and the industry cooperatively embarked on a rush project for “smart” or at least “softer” bags. It was a tough choice for Washington — do you mandate protection for the young, the elderly and the small who can’t help themselves or for the adult male fools who refuse to fasten their belts? Washington obviously wanted a “smart” bag that could tell the difference in the split second before banging—and with time and testing the industry provided it.

Now, you may well ask, how does all this folderol fulfill the claim that the interlock was the world’s greatest safety device?

Based on my own frustrating experience driving such a car in everyday use, I’ve always thought the interlock device was the perfect answer to the second biggest automotive safety problem, the drunk driver. Even though the sequential logic required by the interlock to start the car was simple, it was — and still is — my conviction that drunks would have been unable to handle it. Or perhaps a few more logic barriers could have been built in for those convicted of DUI. This might have overcome the reluctance of judges to interfere with a drunk driver’s livelihood, and thus the horrible contributions of repeat DUIs to highway carnage.

And today, many courts across the country indeed require drivers convicted of multiple DUI charges to have such devices installed in their cars. It is not bulletproof, because drunks can be very devious (such as driving someone else’s car) and to the best of my knowledge there has been little large-scale feedback to safety researchers on effectiveness, but I believe it has great promise.