As Nissan and Chevrolet prepare to launch their groundbreaking electric vehicles later this year, they face a huge task educating the public about just what they are – and aren’t.

Marketing a new car is always a challenge, and something that can cost a maker as much as $100 million for even a relatively conventional product. Now add a battery drivetrain and the challenge – if not the cost – could go up exponentially.

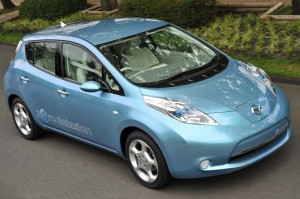

The Nissan Leaf is a pure electric vehicle with a range of about 100 miles and. Nissan calls it the first mass-market electric vehicle – though some might quibble with that and point to the battery cars the industry tried to push in the early 1990s.

The technology under the hood of the Chevy Volt is even more unusual. General Motors calls it an extended-range electric vehicle (rather than a plug-in hybrid, a difference a bit more than just semantics). The Volt can travel about 40 miles on a full charge. At that point, a small gasoline engine starts to provide up to 300 additional miles. When it runs out, pull into a fuel station to fill up for another 300 miles, just like a traditional car. It’s still an electric vehicle because the gasoline engine drives a generator, so it never directly powers the vehicle.

Getting consumers to understand those concepts is a huge challenge for the two automakers as they approach the limited launches of these new kinds of vehicles. And it’s complicated by concerns about what the technologies actually do – something Rush Limbaugh’s recent, misguided rant about Volt shows won’t be easy to overcome.

Marketers will not only have to explain the technologies, but help filter out those who would and wouldn’t be good candidates for the vehicles, what they can expect to do with them and how their higher initial price premiums will fit into a buyer’s budget..

Rich Thomaselli, who analyzes advertising strategy for the industry publication AdvertisingAge, said one ad could feature a husband kissing his wife goodbye before heading off to work. The wife asks “Do you have your lunch?” “Yes,” the husband answers. “Do you need money for gas?” “Nope, don’t need money for gas.” The scenario could be played out repeatedly with the husband finally saying “I don’t need gas money anymore.”

“Part of the advertising will be more anecdotal in nature,” Thomaselli predicted.

So far, Thomaselli said he has been impressed by the Volt’s limited advertising, which was done by Goodby, Silverstein & Partners, Chevrolet’s new advertising agency. The first ad is very stark, relies heavily on text and does not show the car. (Click Here to take a look.)

“I thought that advertisement was just fabulous,” Thomaselli said.

Nissan’s Leaf advertising is focused on Apple’s new iAd platform for the iPhone. It’s a cool new technology to advertise something that is, itself, a cool new technology.

Thomaselli said that GM and Nissan probably won’t want to do any comparison ads – one of the great automotive advertising traditions – not comparing Leaf and Volt, anyway, since the two are so different, but he added they will have to find a way to help the public understand those differences.

“The general public probably looks at both of them and thinks they’re both plug-ins and thus, the same car,” Thomaselli said.

Nissan and GM also are facing the prospect of explaining why buyers should pay more for a car than they are accustomed with the benefit being reduced fuel costs. Since GM announced that the Volt would be priced at $41,000, (Click Here for the full story), the Internet has been filled with commentators suggesting the price is too high. But when buyers take into consideration all of their vehicle costs – including fuel, the Volt looks a lot better.

The Leaf faces a similar problem, although at a price of $32,780, consumer response has been better than that for the Volt. Purchasers of both cars are eligible for a $7,500 federal tax credit, plus state and local taxes in some areas – and both makers are promoting lease prices of $350 a month, which should soften the blow for Volt, in particular.

Selling any battery-based vehicle on price can be a challenge, in part because the advantages depend on a mix of driver behavior, gasoline prices, local utility rates and other factors. Under the most ideal conditions, however, industry experts contend it can cost as little as a penny or two per mile to run on electricity, as little as a tenth as much as driving on gasoline.

Thomaselli said bringing in the cost of fuel will hit consumers in their wheelhouse. “You don’t need to pay for gas.”

Have they figured out what kind of gas mileage the Volt gets?

Jim,

My understanding is we’ll have to wait until closer to launch for the official EPA numbers but I’m tentatively estimating somewhere in the mid-30 mpg range (combined) and 40+ in City driving, which is where hybrids always do better — in contrast to conventional gasoline-powered vehicles. Chevy has not formally revealed the size of the Volt gas tank, though it is likely somewhere between 8 – 10 gallons, and with them promising about 300 miles on gas alone, well, you can do the math.

We’ll press our contacts for a better answer and post it here once we get it.

Paul A. Eisenstein

Publisher, TheDetroitBureau.com

I’m not sure that it’s solely a consumer perception problem, as the article indicates, as in “Getting consumers to understand those concepts is a huge challenge.”

Consumers seemed to have no great difficulties taking technological leaps for reproducing their music. They leapt from vinyl records to cassettes, then to CDs and finally to iPods. The technology for getting a music download is a thousand times more complicated than clicking on the screen. However, most users can’t even conceive of what is going on. They get their music, they’re done.

My point is that I think the public will adapt if the adaptation makes any sense. They don’t need to understand how the car works if they want to drive it. If people don’t want the car, you can’t sell it — you’d have to give it away.

JM

Hi, JM,

I don’t disagree that once the public learns about new technology that makes sense — meaning good functionality, acceptable price, etc. — consumers have shown a willingness to adapt and accept, but the new battery technologies (plural) are difficult for even some in the media to understand. I have spent a significant amount of time discussing the merits of hybrids with consumers and I have only rarely seen anyone who understands how to do the basic math to figure out if and when the technology is right for them. When you add in plug-ins and battery cars — heck, when you ask buyers to differentiate between plug-ins and E-REVs — you’re going to have a seriously confused market and for some time. Rush Limbaugh couldn’t come close to getting the facts straight during a rant about Volt, the other day. I will refine from making any comments beyond the fact that in this case, he is not alone in his lack of understanding.

We’ve seen a number of cases where competing or conflicting technologies create problems, most notably the legendary BetaMax/VHS brawl. In a number of cases, arguably the wrong technology won.

It is going to require some serious education just to get people to understand what the technologies are. Then there’ll be the challenge of helping motorists know how to choose the right technology for them.

Paul A. Eisenstein

Publisher, TheDetroitBureau.com