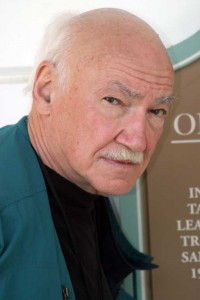

We auto writers are seldom at a loss for words. Heck, we’re often paid by the word. But I think many of us, right now, are having trouble finding the right way to say farewell to Jerry Flint, who passed away of a stroke, this past weekend.

It would be tempting to go with a “just-the-facts, ma’am,” obituary. But, then again, Jerry was never one to stop with the basic facts and figures. It might be equally appealing to grab for a few obvious adjectives to describe a man who spent more than 50 years covering the auto beat. Opinionated is one that anyone who knew Jerry Flint would agree on. Curmudgeon is likely another.

But neither approach tells the full picture of a man who wasn’t just the “dean” of auto writers, as his journalist son, Joe Flint, suggests. For all his talents, as well as his flaws, Jerry Flint fell somewhere between conscience and contrarian. He accepted no easy answers and didn’t tolerate them from friend or foe, industry leader or media colleague. It is that role, along with his wit and wisdom, his bawdy asides – and the encouragement he offered me routinely over the 30 years I can count him as a friend that I will personally miss.

It’s tempting to suggest that Jerry Flint was born to cover the auto industry. A Detroit native, he grew up in what he described as a “workers hillbilly neighborhood.” Detroit had been a boom town, but by the time Flint was born, on June 20, 1931, it was deep into the Great Depression, and the Flint family would walk, rather than ride the streetcars, to save a few nickels. When it came time to go to college, he didn’t stray far, enrolling at Wayne State University, which was then Detroit’s city college.

But it was the midst of the Cold War when Flint graduated, in 1953. Too late for the Korean conflict, he landed in Hamburg, Germany, a member of military intelligence. An oxymoron, perhaps, but a good training ground for a man who liked to understand what made the world around him tick.

Returning home, Flint landed a plum job as Detroit correspondent for the Wall Street Journal. He stayed there until 1967, when he was named Detroit bureau chief for the New York Times. It was a multifaceted job, one requiring Flint to cover a wide range of topics, including the ’67 Detroit riots, where he saw many of the streets of his childhood go up in smoke and rage.

The Times convinced Flint to move to New York in 1973 — the city where he would spend most of the rest of his life – where he worked as chief labor reporter and an assistant editor. But six years later, he made one last jump, this time to Forbes, the idiosyncratic business journal where he’d spend the rest of his official career. Flint worked briefly in Washington, in 1979, before returning to New York.

Those, ma’am (and sir) are the facts. But the real Jerry Flint is a story of many shades of gray in-between. What no one can dispute is Jerry Flint’s love of the car business, and his ability to connect with the industry’s men and women, from the lowliest line worker to the loftiest of executives. He treated them all pretty much the same way: with a balanced mix of curiosity and skepticism.

One former senior Big Three executive recalls Flint as a “cantankerous contrarian. Tried to get me fired once,” he says, but like many who crossed swords with the veteran journalist, over the years, the executive recalls “We became friends.”

But even with his friends, Jerry Flint was never one to back down. A lunch could, at times, start to become a lecture. And when he got on a roll it was good to step back a few feet, as one veteran public relations executive, then an industry newcomer, found out during a discussion over Indian food. “I had to clean the lentil mud off my glasses, but it was worth the PR lesson.”

Once, when he served as president of IMPA, the New York-based auto journalist group, he presided over a speech by a senior industry official. When the executive waffled during the obligatory question-and-answer session, Flint started offering his own, much more insightful observations instead.

His views weren’t always easy to take, especially for those on the industry side, like the General Motors managers he addressed, back in early 2001. “GM executives,” he declared, “don’t seem to understand that the art of the auto business is building desirable vehicles, not killing models and closing plants.” Nearly a decade before the giant automaker, long the world’s largest, went bankrupt, Flint told them, “You are badly led, with an organization that doesn’t work.”

A fiscal conservative, Flint could be equally harsh on what he saw was the waste of tax dollars for government-funded research “by anyone with the knack for filling out a government grant application (that led down) blind alleys that they otherwise would have skipped.”

When he reached his 65th birthday, Flint retired from Forbes. Officially, anyway, with a lavish send-off from an unlikely assortment of journalists and senior executives – including then-Ford Chairman Alex Trotman, whose seemingly tongue-in-cheek comments laid out his hopes that Jerry would find something else to do in retirement. But it wasn’t going to be. Flint not only knew what he was good at but knew it was the thing he loved most.

He continued writing columns for Forbes, and for Ward’s AutoWorld, and for an Internet magazine I founded and published until several years ago. As Flint’s health deteriorated, over the years, his wife, Kate, would often call editors and ask them to slow Jerry down. It didn’t matter what we asked for. The words would show up, early on by fax and then, belatedly, by e-mail as he mastered the new technology.

There are plenty of folks who’d qualify for prodigious, especially in the era of the copy-consuming Internet. Jerry Flint was, if anything, a bit of a throwback to an era when credibility was earned over time, by proving yourself worthy one column or story at a time, not simply by showing up in print.

His list of awards could readily fill an obituary on their own. He was named one of the Top 100 Financial Journalists of the Century by The Journal of Financial Reporting. Flint won the Gerald Loeb Award for Distinguished Business and Financial Journalism, in 2003. But the honor I recall him talking about with the most excitement was being named one of 40 finalists to be NASA’s first journalist in space.

The program came to a sudden halt when the Challenger shuttle exploded during lift-off, but had he lived long enough, I would not have been surprised to see Jerry Flint find his way about the Virgin Galactic, the Richard Branson venture to begin sub-orbital commercial space flights. Flint likely would have spent even his minutes in zero gravity pinning Branson to the wall for a clear explanation of his business case.

Jerry Flint is survived by his wife, Kate McLeod and four children from a previous marriage, as well as five grandchildren, a sister and a niece.

He also leaves a deep gap in the journalistic community where he so ably served as a dean for more than half a century.

In lieu of flowers, please send donations in memory of Jerry Flint to the Overseas Press Club Foundation, 40 W. 45th St., New York, N.Y. 10036.

This is sad news and a great loss.

Well said, Paul..

Jerry was unique and special… fun to read and fun to be with.

We always told GM executives who were leery of granting an interview to Jerry… “Don’t worry. Just listen. He will tell you how to run the business.”

Paul,

What a great summary of an extraordinarily complex character.

Those of us on the PR side who worked with Jerry have plenty of war stories to tell. We usually lost the war, but we’re still proud of the battle scars.

Dan Bedore

Hyundai Motor America

I met Jerry while i was a Forbes. A gentleman and kind to young reporters. In addition to his knowledge and craft writing about automobiles, more should be said about his support of others in the field.

My condolences to his family.

Paul,

You got it right. The facts do not at all address the essence of Jerry Flint; they simply frame his life, setting some markers to follow his progress. Jerry could be exasperating for those in my (automotive PR) business (not for me – I loved his bombastic style) because of how industry types reacted. Jerry did not simply put their feet in the fire, he roasted toes and bunions! He suffered fools badly and was never afraid to challenge anyone – from Iaccoca to Lutz to Smith. No one, no entity was off limits. And he did it with knowledge and perspective, with wit and color.

He once spent nearly three hours (during a mid 80s lunch for which I picked up the check) explaining how I represented the three worst car companies in the world (American Motors, Renault and Rover). Despite the theme, I left the restaurant happy and a lot smarter.

He will be missed by all.

Paul,

Very well written. I have such fond memories of Jerry, spending countless hours listening to him shrug off the spin various executives tried on him over the years. Jerry worked for Ford once, and he knew where all of the bodies were buried in Detroit and Dearborn. I learned a lot from him. I saw him earlier this month at the Explorer reveal in New York. We were both shaking our heads at the state of the industry. I was the one who suggested he run for president of IMPA, and he served our organization well. I will miss him terribly.

– Joe

great piece, paul

Thanks, Paul. For me, this loss will be most acutely felt when Jerry is not seen shuffling around NAIAS 2011…always ready and willing to shuffle right in front of me and then scowl when I have to slow a step or two to let him pass. Why do we love crusty old guys like Jerry so much?

James Bell

kbb.com

Folks,

Kate McLeod has asked me to note the following:

In lieu of flowers, please send donations in memory of Jerry Flint to the Overseas Press Club Foundation, 40 W. 45th St., New York, N.Y. 10036.

Thanks,

Paul E.

Paul,

A great way to sum up Jerry’s career. We all can learn from him. I feel the same as you. He will be missed. NAIAS won’t seem the same without him.

Richard Truesdell

Editor, Chevy Enthusiast

Editorial Director, automotivetarveler.com

What I loved most about Jerry was his depth of knowledge and his passion for the industry. Even when I thought he was totally full of it — and there were a few times — he was arguing from a solid base of knowledge and experience, and he passionately cared about the companies he was covering. In an era where cable TV and the blogosphere have created the culture of the instant expert, Jerry was a throwback of the best kind, and I will really miss him.

One of the challenges writing about Jerry is recalling all the anecdotes over nearly three decades of knowing him. One of my favorite that got left out of my remembrance:

Some years ago, Jerry was covering negotiations at Chrysler’s old headquarters, in Highland Park. He was told to get some quotes for a piece, but nobody was talking in any way he could use. So he took a piece of chalk and drew a circle on the ground at the K.T. Keller corp. office. He stepped inside and made one of his typically pithy observations. It soon showed up in a story, attributed to “a knowledgeable source in a well-placed circle.”

Paul E.

Paul: Very well-done piece. Befitting the subject. I recall my first Jerry encounter as a completely passive witness at a Buick lunch about 20 years ago. It was at Tavern on the Green in NYC. Being a young, green writer (I showed up in a sweater and not a jacket and tie!), I clammed up thoroughly. However, I noted that other people — people I knew of by having read their articles — clammed up when Jerry spoke, as well. I can probably count on one hand the times when Jerry’s opinion or take on something was incorrect, but a symphony orchestra doesn’t have enough fingers to count how many times he was correct and insightful.

Paul, a beautiful piece to honor Jerry. Many thanks.

Paul — Thanks for Jerry’s ode. I had more than a few conversations with him that started with his asking a question, and ended in his lecturing me about the ills of the past four decades of degenerate automotive leadership. He said they would never listen, but, I always did. I learned to love his passion, and respect his experience. I’ll miss Jerry. One of a kind, to say the least!

Thanks Paul. You’ve really captured the man here. My first impression of Jerry came from my first interaction with a group of automotive journalists at a product launch. I was a chief engineer at Ford leading the long-lead tech briefing for the all-new Expedition…late 2001 or early 2002. After my presentation, we took some group Q&A, then met informally with journalists around the technical displays. I didn’t know Jerry (or his reputation), but learned all I needed to know from an exchange that went something like this:

Jerry: “Why in the world did you keep the ignition switch on the steering column? No one likes that. Customers want the ignition switch in front of them on the dash board where they can easily get at it.”

John: “Yeah, I know…but we had to use a carryover steering column to pay for some other stuff, like that really cool fold-flat rear seat.”

Jerry: “Don’t give me that bull&*!#. You spent a billion dollars on this program. It’s your job to make things right for the customer. I don’t care about your internal issues. Next time, get it right.”

I found out later that that was Jerry Flint. He was right of course on the ignition switch. When I met him again a few years later, after I came to Hyundai, I recounted that story, and he remembered it (with a twinkle in his eye and a bit of a smile). Every chance I could at launch events, I’d sit with Jerry at dinner and soak up his straight-shooting point-of-view.

He mellowed a bit in his last few years, but he was always a great automotive journalist, dedicated to his craft, insightful and provocative. I wish we had more like him.

Paul

Great piece on Flint. Still hard for me to believe I won’t be seeing him at previews and auto shows any more. Cantankerous and kind, harsh and funny, a unique individual with more automotive knowledge in one corner of his brain than most of us have in our entire heads. Thanks for your remembrance, brought back a lot of Jerry for me.

Paul:

Thank you for this eloquent tribute. Jerry’s was indeed a life well lived — a passionate and sagacious scribe who had the good fortune to travel the world savoring the simple abundance of being home with those he loved and loved him. He will be missed, but not forgotten. My heartfelt condolences to Kate and the rest of the family.