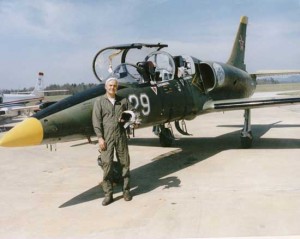

Maximum Bob Lutz, getting ready to strafe the competition

To friends and foes alike, he’s “Maximum Bob,” and there’s little doubt that in a half-century career, Robert A. Lutz never shies away from an opportunity to push things to the limits – whether helping develop a new product or racing it. His resume reads like a Who’s Who of Automakers, with names like BMW, Ford, Chrysler and, now, General Motors, where he serves as vice chairman and “car czar,” reporting directly to CEO Rick Wagoner.

The Swiss-born former U.S. Marine fighter pilot would likely see his tenure at the automaker’s downtown Detroit headquarters as the toughest fight of his career. He’s struggled to break through GM’s well-entrenched bureaucracy and get the company to refocus its efforts on making the world’s best cars and trucks. There’ve been some rewards, with newer products, like the Chevrolet Malibu, winning rave reviews. And the Chevy Volt, an “extended-range electric vehicle,” has become a symbol of the industry’s evolution from gas-guzzling SUVs to high-mileage hybrids, plug-ins and pure electric vehicles.

We had the chance to speak with Lutz about a wide range of topics, including the Volt and electric technology. It’s a curious topic for a discussion with the septuagenarian executive because Lutz is an outspoken skeptic when it comes to global warming, but he’s also hot on the subject of battery power.

Q: Any guess, by 2020, what percentage of your vehicles will have a Volt-like powertrain?

Lutz: No, it depends on whether we get a national energy policy, a stable price for fuel, which would permit for planning. Every six months, we’re stupid idiots because (prices change radically and) we should have planned in the other direction. We were stupid when we didn’t plan to build for light trucks. Then we were stupid when we didn’t see fuel hitting $4 a gallon. Now, you can’t give hybrids away, and dealers are saying, “Enough, but we’ll take a few more Tahoe (SUVS).”

Q: You used the Detroit auto show to reveal the battery supplier for your new Chevrolet Volt extended-range electric vehicle. What makes one supplier better than another?

Lutz: Oh, it’s suitability of the chemistry, experience in producing that type of battery, energy storage, speed to market, willingness to accept warranty responsibility – and last and probably least, price. We weighed a huge number of variables as we always do.

Q: Are we actually seeing some real breakthrough developments?

Lutz with the original Chevrolet Volt concept vehicle

Q: There are some folks, including the Chinese maker, BYD, which is exhibiting at the Detroit show, which are talking about pure electric vehicles getting 200, 300, even 400 miles range. Are they onto something?

Lutz: No, no. I don’t think anyone’s onto anything beyond lithium chemistry. I think they’re looking at the same thing – but cramming the vehicle full of batteries. And they’re probably using a much larger amount of the (stored energy in the) battery. When you’re talking 300 mile range on a battery, I hope I’m around to see it, but I don’t see anything like that.

Q: You’re bringing an unproven technology to the market, and in low volume. How does that make money?

Lutz: It’ll be proven by the time we bring it to market. And the volumes aren’t that low. We’re talking about 60,000 worldwide. And as the costs come down, I’m hopeful it won’t be a zero-profit equation forever. If we can bring other brands (Cadillac with the Converj), to market, we can command a higher price and make some money more quickly.

Q: Are you concerned that the plug-in Prius will out-perform Volt?

Lutz: Oh, no, no, no, no, no. The plug-in Prius, at best, will have 8 to 10 miles range purely on battery power. That’s the difference between a plug-in and an extended-range electric vehicle. Prius is a vehicle driven either off the gasoline engine or the battery, and when the charge runs down, the gasoline engine takes over, like a normal hybrid. Volt is never a normal hybrid. It’s always an electric vehicle. It will initially have 40 miles range, and then the gas motor kicks in as a generator, but the wheels are always driven electrically.

Q: So what’s the solution?

Lutz: Maybe we need a tax that adjusts when petroleum prices shift to give us a stable price at the pump. I actually look forward to having a federal car czar because we’ve never had a point person in the administration to have a decent conversation with. There’s been no one with the concerns of the car companies at heart. If the czar diligently reports back (to Washington), this may lead to a sounder energy and transportation policy in the future.”

Q: You’re calling for a gas tax? Do your competitors agree?

Lutz: I don’t want to sound like I’m advocating a gasoline tax, because that’s a very unpopular thing to do, but we have to have a stable price and a planning basis. And if we truly want to drive this nation to greater fuel efficiency and independence from foreign oil, we have to make the customer desire more fuel-efficient vehicles. And at $1.50 a gallon, that just won’t happen.

Q: Can you imagine a day when electric vehicles take over? Where could we be by 2020?

Lutz: There are some vehicles for which electric powertrains just simply don’t work. And if you’re talking 2020, that’s just 11 years away and I just don’t see the electrical infrastructure, technology and battery manufacturing growing enough to have the bulk of vehicles go electrical by then. By 2020, we might be at 20 to 25 percent electric, counting a vehicle like the Volt.

Q: What about hydrogen?

Lutz: It still may be the long-term solution but I think it will come later than batteries. The advantage for batteries is that the installed infrastructure is already there and you could easily put outlets with meters in a parking structure. It’s infinitely more easy with electricity than with hydrogen. But you can get a better range with hydrogen than batteries.

Q: Is there a positive side to the current financial crisis?

Lutz: A period of financial crisis forces us to separate ourselves from things that are nice to have versus those that you must have. And it separates the clutter. A perfect example is our auto show stand. When we had the money, we had a holographic stand for Saturn, which cost us probably $500,000. This year, the total stand’s cost is down by 50 percent and has never looked better and more reflective of General Motors’ excellence. It comes from not having the money to do dumb things.

Q: What about eliminating brands, something you’ve resisted, at GM, for years?

Lutz: When you’re under severe financial stress and have loans you’re going to have to repay, you start prioritizing what’s important. And, when you do that, you take a look at the brands you’d like to have, but haven’t been paying their way – one of the brands at the top of the list is Saab, which has been on General Motors’ life support for 20 years is Saab, with an endless string of losses. Frankly, we have to undertake a strategic review of Saab, which could mean a lot of things. Another brand is Hummer, which seemed like a perfectly good brand, at one time, but which has become a poster child for wretched excess. The brand has just acquired baggage it’s impossible to get rid of. And we have Saturn, a very good brand, with arguably the best product line-up of any brand in the country. But for some reason, the division has been unable to deliver the huge volume needed to pay that investment off. So Saturn has to be reviewed. And finally, there’s Pontiac, which will be pared back. It will never get another crossover, SUV or minivan again.

Q: Saturn seems the division that could still be saved.

Lutz: Yes, it could. Strategic review means we’re reviewing all alternatives and have not made a decision.

Q: Did GM kill Saturn when it had a chance to grow it, in the early years, but refused to provide the product it now has?

Lutz: I wouldn’t be that harsh. But we created a baby that was growing very healthily. And then, when it was six, we told it to go get a job because we wouldn’t feed it anymore. It was naive to assume that a brand like Saturn could become profitable (early on) with only one product.