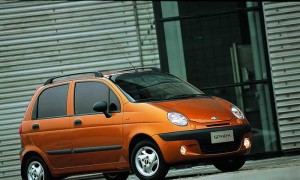

GM spent years debating whether to build a U.S. version of the Asian Chevrolet Spark, shown here. Concessions from the UAW now will make it possible. GM also will keep several shuttered assembly lines mothballed, rather than closing them permanently.

The United Auto Workers has used its residual clout to force General Motors Corp. to build a new class of small, so-called “B-” class subcompact cars in the United States.

UAW president Ron Gettelfinger said the union now has a firm commitment from General Motors to build a new small car in the U.S., instead of China or South Korea, as had been planned. The UAW had objected to GM’s plans, both publicly to Congress, and privately to the President Barack Obama’s Auto Task Force, which is now the decisive voice shaping auto policy.

“Small cars represent one of the fastest-growing segments in both the U.S. and around the world,” said Fritz Henderson, General Motors President and CEO as GM confirmed the new small car will indeed by built in the U.S. “We believe this car will be a winner with our current and future customers in the U.S.,” Henderson added.

The conventional wisdom has long held that American manufacturers cannot make money on small cars, especially if they are built in the U.S., where labor rates and productivity have been non-competitive with foreign, and especially Asian manufacturers. But the numerous concessions made by the union, in recent years, and especially recent givebacks meant to turn the domestic industry around, have changed the equation.

“There is absolutely no reason “B” and “A” class cars can’t be built right here,” said Gettelfinger, during a press conference at UAW headquarters, in Detroit. “There is no reason for these companies not to build small car is this country and we’re going to remind them of it every day,” he said.

“There is absolutely no reason “B” and “A” class cars can’t be built right here,” said Gettelfinger, during a press conference at UAW headquarters, in Detroit. “There is no reason for these companies not to build small car is this country and we’re going to remind them of it every day,” he said.

Gettelfinger has quietly — and sometimes not so quietly — prodded automakers, over the years, to build more small cars in the U.S. The new commitments, first from Fiat, and now from GM, represent something of a personal triumph for the union chief, who has dismissed the notion that America can’t build small cars at a profit as out of date. Ford Motor Company will likely feel union pressure next.

Meanwhile, GM has agreed that the other two assembly plants that it was preparing to close will be protected. Instead of being shuttered permanently, they could be closed temporarily and revived when consumer demand for new vehicles picks up, said Cal Rapson, the union’s top negotiator with GM. “The viability plan was built on sales of only 10 million units,” said Rapson, indicating the union successfully argued with the Auto Task Force that it should retain flexibility, in the form of some additional capacity, to satisfy demand as the economy recovers.

Without the plants, GM would have been left short in a recovery, he said.

Union concessions, including those approved this week by UAW members employed by GM, have sharply reduced labor costs in the U.S. The new contract is expected to save GM at least $1.2 billion annually.

The contract also includes a ‘no-strike’ provision and major changes in work rules and job classifications long sought GM. The contract is also designed to reduce the number of skilled trades in GM plants, which has helped drive up the company’s labor costs over the years.

The no strike provision is offset, however, by the fact that the union, or more precisely, the Voluntary Employee Benefit Association that is answerable to the UAW, will have a seat on GM’s reconstituted board of directors.

Gettelfinger also indicated he is prepared to keep up the pressure on the Obama Administration. The union will continue to try and block any kind of trade deal with South Korea that doesn’t open up the Asian nation, which currently maintains a highly restricted automotive market.

The U.S. can’t continue to run major trade deficits with it major trading partners, Gettelfinger insisted. In a curious turn, that was a point that GM’s retiring Vice Chairman Bob Lutz stressed, Thursday, during a meeting of the Detroit Automotive Press Association. Once again, the question of a national industrial policy, which all of the nations exporting to the U.S. have used to target industry after industry here while protecting home markets, is becoming a political issue.

“Maximum Bob,” insisted that lopsided currency exchange rates need fixing, while trade barriers have to be broken. It’s the same argument that Detroit has made for decades, but this time, with Washington suddenly holding a major stake in the long-term health of two of the Big Three, “for the first time,” said Lutz, referring to the White House, “they’re listening to us.”