It was supposed to be the car that would help save the troubled brand. But instead, it was the last car Oldsmobile would build. This Tuesday marks the 10thanniversary of the demise of the once popular brand, a decade since a dark red Alero sedan rolled off the line at the old Lansing Car Assembly Plant as the last car Oldsmobile would ever build.

Lansing had been the home for the brand for more than a century, Ransom Eli Olds cobbling together his first motorized carriage in his father’s shop in Michigan’s capital city in 1897. The Curved Dash Oldsmobile he started producing four years later was to become the country’s first truly mass-produced automobile, an early pop culture sensation that inspired the 1905 hit song, “In My Merry Oldsmobile.”

Purchased by General Motors in 1908, Oldsmobile would eventually sell as many as 1 million vehicles a year. But as the new millennium approached, the brand was clearly past its prime, and like the proverbial canary in a coal mine, it was sounding the alarm for a crisis that would ultimately drive GM itself into bankruptcy.

R.E. Olds’ first cars were sold through “Olds Motor Vehicle Co.,” but the firm went through a series of changes in quick procession, surviving a devastating 1901 fire that destroyed all but two early prototypes. The shortened name, Oldsmobile stuck, even as the company was sold to GM – becoming its second brand – in 1908.

Ransom Olds himself was already gone. Forced out in 1904, he went on to form the short-lived REO, perhaps better known today for the model it once produced that inspired the rock band REO Speed Wagon.

(GM CEO Mary Barra named to “Time 100″ list of world’s most influential people. Click Here for the story.)

For decades, Oldsmobile served as one of the country’s most elite brands. Though it didn’t have the luxurious cache of Cadillac, Olds was where General Motors often introduced some of its most significant new designs and technologies. That included such breakthroughs, like the “Rocket” engines of the 1940s and ‘50s, as well as the 1966 Oldsmobile Toronado. With its then-revolutionary front-wheel-drive powertrain layout, the Toronado was named Motor Trend’s Car of the Year.

By the early 1980s, even as GM had begun to lose market share to its increasingly energetic import rivals, it seemed like there was no limit to Olds’ potential. Its expanding line of Cutlass-badged models were helping boost the brand’s sales to more than 1 million annually – spurring then-General Manager Bill Lane to cockily tell a group of media assembled for the annual Olds product launch that, “If I could sell more cars, I would name my daughter ‘Cutlass.’”

The strategy didn’t work for long, nor did an expensive and high-profile ad campaign that followed. Anchored by the tagline, “This is not your father’s Oldsmobile,” it became an object of ridicule.

Olds entered an increasingly rapid freefall. By the beginning of the next decade the brand’s future was the stuff of whispers and rumors – then open speculation. After initially denying the threat, John Rock, by then Lane’s successor, declared himself, “one pissed-off cowboy,” and announced Olds would launch a series of new products designed to win its audience back. “We’re going to throw some s*** on the wall and see what sticks,” the colorful Rock went on to suggest.

(Hammered by recalls, GM barely in the black for Q1. Click Here for more.)

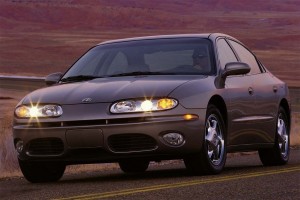

The planned revival began with the strikingly styled Oldsmobile Aurora which generated unexpectedly strong reviews and an initial burst of sales. As the brand celebrated its centennial in 1997, there was some cautious hope. But when the maker launched an updated version of Aurora, adding the Alero to the line-up, critics were far less kind, the New York Times dubbing the smaller model an example of “white-bread mediocrity.”

The New Millennium began badly. By December, the once high-flying Olds had sold barely 265,000 vehicles, down more than 18% from an already miserable 1999.

And so, in December 2000, former GM CEO Rick Wagoner announced plans to phase out Oldsmobile over the next four years. Ironically, his news conference was held on the same day reporters had gathered to hear about Olds’ newest SUV, the Bravada, generally considered the most attractive of a line-up of midsize GM utes.

“We decided we couldn’t put enough marketing resources into Oldsmobile” to save it, contended Ron Zarrella, at the time the president of GM’s North American Operations, “considering we were in a money-losing position.”

Ironically, the failure of Olds also set in motion the collapse of the brand-centric strategy Zarella, a former chief of contact lens company Bausch & Lomb, had inaugurated. And it signaled the ultimate, near-fatal collapse of GM itself.

The Bravada and Aurora were already gone by April 29, 2004, the day that cherry red Alero rolled down the assembly line.

GM officials hoped that by dropping Oldsmobile they could shift increasingly scarce resources to developing and marketing products for GM’s eight surviving North American brands. But even that goal was out of reach, it soon became apparent.

By late 2007, GM’s CEO Wagoner would accompany his fellow Detroit chief executives to Washington to beg for a federal bailout. Ford would ultimately navigate its own way out of the deep recession the industry – like the rest of the economy – was falling into. GM, like Chrysler, would survive only with an infusion of federal cash.

In the process, GM would drop four more brands, Pontiac, Saturn, Saab and Hummer, leaving it with just four marques for its U.S. showrooms. Oldsmobile, it turned out, was the canary that warned of GM’s near-death experience.

(New car sales picking up momentum in April. Click Here for the news.)